Context Clues: Why Did They Pass Out?

Rachel Clark2024-01-27T10:55:01-08:00

Last Updated: January 27, 2024

Context Clues: Why Did They Pass Out?

Unraveling the Mystery

By: Rachel Clark, Education Manager

Edited by: Erica Darragh, Outreach & Chapter Development Coordinator, DanceSafe

Alex Krotulski, PhD, Associate Director, Center for Forensic Science Research and Education

Alexander/a Bradley, MPH, Outreach & Community Engagement Manager, HIPS

Luke Rowe, Paramedic, HCPC UK

This article, although edited by a medical professional, is not medical advice or official guidance.

This article contains mention of death, overdose, assault, and gore. Reader discretion is advised.

We’ve all seen the shocking tweets, viral texts, and sensationalist headlines claiming mass overdoses at parties. We’ve seen claims of “bad batches” without substantiation, ridiculous made-up drug names (“happy meals..?”), and wild statements about fentanyl ending up in toilet paper or a festival’s water supply.

More importantly, though, we’ve seen people respond to each other’s freak-outs, pass-outs, and physical upset with compassion and concern, in an attempt to care for one another in the face of uncertainty. This guide is here to provide resources and information to support you in that role.

It can be very confusing and frightening to have to make guesses about why someone might have lost consciousness, but assuming someone’s medical status – especially telling others that someone overdosed or passed away – can:

- Incite crowd panic (see: Astroworld);

- Spread unsubstantiated rumors that make it harder to tell what really happened;

- Cause additional social, emotional, or physical harm to the person in question.

Similarly, assuming that someone is “just resting” or “sleeping it off” could end up costing their life.

It’s really important to know the information in this guide, not only to prevent passing out in the first place but also to respond to and report on the situation accurately.

- Someone who passed out from heat stroke will not benefit from naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal agent (brand name Narcan).

- Someone who passed out drunk from exhaustion, not alcohol poisoning, probably just needs to be monitored and rolled onto their side in case their airway becomes blocked.

- Someone who passed out might receive CPR from a well-meaning onlooker, even if they don’t actually need it.

The fact of the matter is: it’s pretty normal for folks to pass out when they’re in stressful environments, and it happens all the time. It’s understandable that people are scared because of fentanyl and the drug supply. It’s important, frankly. But part of drug education is recognizing that not every frightening physical experience is related to drugs at all; sometimes the human body just doesn’t like what’s happening. Sometimes a drug you’re very experienced with happens to treat you differently without warning, and it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s a “bad batch.”

People deserve to know what happened to them, and you can be a part of that.

What’s the deal with this guide?

This guide will get into the gritty details of how to evaluate, respond to, and communicate about people passing out in all kinds of situations. We’ll talk about overdose, heat illness, seizures, syncope, and other tidbits you might come across when you’re first on the scene. This is a next-level rave parent’s handbook.

Terminology:

- Unconscious or unresponsive – not awake (“passed out”).

- Respiratory arrest – someone’s not breathing. Will lead to cardiac arrest if there’s no intervention.

- Cardiac arrest – someone’s heart has stopped beating. This also implies that the person is not breathing.

- Heart attack – supply of blood to the heart has been blocked. (A heart attack is not the same as cardiac arrest. Heart attacks often lead to cardiac arrest.)

- Depressant – a class of drugs that reduces central nervous system activity.

Consciousness is evaluated on a scale:

- Alert

- Confused

- Responds to voice

- Responds to pain

- Unresponsive

Why do people usually pass out?

Environmental conditions like heat, stress, panic, hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), dehydration, pre-existing medical conditions, seizures, and physical responses to distress are probably the most common reasons why people lose consciousness at shows. Each of these will be impacted in some way by the drug(s) someone has consumed.

These environmental factors may lead to “syncope” (sink-oh-pee), which is the medical term for fainting. In extreme cases, loss of consciousness may become coma. Each of these states can look and feel like being altered on drugs. Many people underestimate the power of a body out of balance and assume that their loss of consciousness was drug-related instead.

Okay, what about overdose?

An overdose happens when someone’s dose of a particular drug is too high for their body to handle. A quantity of a given drug might affect two people very differently, so “overdose” won’t look exactly the same for everyone.

- Billy and Sally are both taking a dose of the same batch of meth orally.

- Billy finds that 60 mg is their sweet spot, while Sally finds that 60 mg puts her in a state of “overamping” where she’s experiencing extreme paranoia and arrhythmia.

- Overamping is a great example of how an overdose state has many presentations. In this case, Sally simply took too much and is feeling very distressed and physically unwell.

Someone might also take the same dose of the same drug under different circumstances and have different results each time. Many overdoses happen when someone takes their normal dose in a new environment, or after a tolerance break.

- Billy takes a few weeks off of using meth, so their tolerance goes down.

- They try taking 60 mg again, this time on an empty stomach at the end of a long and stressful day at work.

- These circumstances are hard on their body, and Billy ends up in an uncomfortable overamping state.

When we say “overdose,” we basically mean “the point where things have started to go wrong because the dose was too high for someone in a given situation.”

CAUSES OF PASSING OUT

Depressant Overdose

Depressants slow down the activity of your central nervous system. Depressant overdoses mainly become lethal when someone’s breathing slows to the point that their heart stops.

Depressant overdose isn’t always life-threatening, but it can be. The idea is to intervene before 1) someone’s respiration slows to the point that their heart stops, or 2) someone asphyxiates (chokes) on anything. This intervention will look a bit different depending on the specific depressant(s) involved in the overdose.

The most common form of overdose at events is alcohol overdose (alcohol poisoning). Opioid overdose remains uncommon in nightlife and party settings. It should not be automatically assumed that someone at a party is experiencing an opioid overdose unless the circumstances match a specific checklist of signs, which we’ll get to shortly.

For now, it’s important to know that the class of drugs known as depressants – which includes alcohol, opioids, benzos, GHB-type drugs, and other less common substances – shares a core set of overdose symptoms, which can make it difficult to tell which drugs are involved.

Symptoms of depressant overdose

- Slowed/stopped breathing

- This is – on average – considered to be an emergency if someone is taking less than seven breaths per minute.

- You can feel someone’s breath by holding your hand over their mouth and nose and monitoring the rise and fall of their chest. (Putting their arm on their chest can help make their breathing more visible.)

- Note: a phenomenon called “agonal breathing” is sometimes mistaken for true breathing.

- This is an automatic reflex that ineffectively attempts breathing in the absence of oxygen, and it means that someone is close to death.

- This is distinct from the “death rattle,” which is noisy breathing due to built-up mucus when a chronically ill person is close to death.

- Slowed/stopped heart rate

- Carrying a pulse oximeter on your person at parties is a very helpful way of evaluating someone’s status if they pass out. A blood oxygen level of 91-95% is cause for concern/monitoring, and a level of 90% or under merits medical attention.

- Slurring and/or slow, uncoordinated movement, if awake

- Inability to be roused (woken) at all is a sign that the situation is likely more serious

- Blue or ashen tint to fingertips, lips, and extremities, which is a sign of oxygen deprivation

The number one risk of depressant overdoses – in general – is insufficient oxygen from respiratory depression, a condition called hypoxia. Hypoxia leads to cardiac arrest if untreated, and oxygen deprivation for 4 minutes or more can cause hypoxic brain injury.

- Different types of depressant overdoses may present with slightly different symptoms.

- Alcohol overdoses frequently involve excessive vomiting and incontinence (peeing yourself).

- GHB-type overdoses frequently involve uncontrollable bouts of falling asleep, or a very deep and rapid loss of consciousness. The person will often deny that they’ve been going in and out of consciousness because they are unaware of it.

- Both alcohol and GHB-type overdoses sometimes involve seizures.

Causes of depressant overdose

The most obvious cause of depressant overdose is taking too much, which – in addition to just basic over-consumption – can happen under any of the following circumstances:

- taking a normal dose in a new environment,

- taking a dose on an empty stomach,

- taking a normal dose after a tolerance break,

- increasing a dose, or

- taking a dose that’s more potent than expected, especially from a new batch.

There are numerous other factors that can cause an overdose situation, however, like mixing with other substances, consuming adulterated drugs, being dosed, contextual differences in the person’s use, and – the hot-button topic – fentanyl contamination.

Dosing on an empty stomach, batch-to-batch variations in strength, medication changes, health conditions, or being a slow metabolizer of a drug can also lead to depressant overdose.

Over 1,100 novel substances have been reported to the United Nations as of December 2021. This doesn’t include the >20,000 FDA-approved pharmaceuticals in the U.S., or the >4,900 supplement ingredients, that are also circulating on the illicit market. Countless combinations of illicit, pharmaceutical, supplementary, and inert substances are being sold in every state in America, and the numbers climb every day.

Illicitly-obtained benzos, GHB-type drugs, counterfeit pharmaceuticals, and other depressants like methaqualone can be particularly risky purchases because there is no accurate at-home testing available for them.

Example: A fake Xanax pill might actually contain an unknown dose of clonazolam, which is much more potent and long-lasting than Xanax (alprazolam) and can cause blackouts at high doses.

Unless a pharmaceutical pill was bought specifically from someone with a prescription, there is zero way of actually knowing how many milligrams – or micrograms – of each active ingredient is in it without sending it to a lab like Energy Control overseas.

- No U.S.-based labs can tell you the quantity of ingredients in a pill.

- Dealers, friends, and suppliers can only guess how much of a given drug is in their pills, even if they think they know.

- This goes for all pressed pills, including Adderall, MDMA, oxycodone, Xanax, etc.

Remember: There is no incentive to make counterfeit pharmaceuticals that contain the promised active ingredient.

Example: A large (but unknown) percentage of counterfeit Adderall contains varying quantities of meth.

Combining multiple types of depressants (alcohol, benzos, opioids, GHB, phenibut, etc.) increases risk of overdose. Mixing these drugs will increase their sedating properties, which greatly increases the risk of respiratory depression.

Combining depressants with certain medications (like SSRIs) can increase drowsiness/sedation, or change the way that your body metabolizes various drugs.

Example: A “prodrug” is an inactive drug that’s converted into an active drug when it’s broken down in your body.

- Heroin is a prodrug for morphine.

- Taking another drug (including medication!) that impacts how heroin is metabolized might impact its effects, or change the amount of time it takes to kick in.

Example: Alcohol and 1,4-B (a GHB prodrug) will exponentially increase each other’s depressant effects. This can slow your breathing to a dangerous degree.

Example: Opioids and benzos, in general, add to each other’s respiratory depressant effects. Since Narcan is only effective at reversing opioid overdose, “benzodope” overdoses tend to be harder to treat.

Depressants are sometimes used to dose people without their consent. This can lead to excessive or very fast intoxication (within minutes, not seconds), with or without passing out.

A note about drug-facilitated assault: While people are indeed dosed without consent, many of the reports we’ve recently received make claims about routes of administration that aren’t really physically possible (GHB sprayed on the skin, etc.) and symptoms that don’t match the drugs that were supposedly involved (feeling faint and passing out seconds later, etc.). Having a well-rounded understanding of the many causes of passing out/blacking out can help narrow down whether someone’s experience was related to drug-facilitated assault, or something else entirely. People deserve to know what happened to them!

Additional reminder: The biggest issue with nonconsensual dosing is the fact that someone chose to dose another person without their consent, not the fact that the drug exists. Being dosed nonconsensually is always an act of violence by another person. Any drugs involved are tools for, but not the root cause of, the assault.

This topic is much more complicated, so we’ll break it down into sections below.

What about fentanyl overdose/poisoning?

Fentanyl can be lethal in quantities as small as 0.5 to 2 mg. It may be intentionally added to certain drugs, or end up there by accident. Unlike pharmaceutically produced fentanyl – which has an excellent safety profile and is very important in medical settings – it is nearly impossible to accurately dose fentanyl that’s been bought on the illicit market because of its potency. This makes the risk of overdose very high.

Since this often happens when someone didn’t consent to taking fentanyl, it’s sometimes known as “fentanyl poisoning.”

Fentanyl is often intentionally cut into opioids like heroin and oxycodone (and sometimes benzodiazepines like counterfeit alprazolam).

- Fentanyl, as an opioid, can emulate and intensify the effects of some of the depressants it’s used to cut.

- People who use illicitly-purchased opioids regularly are often aware that fentanyl is probably in their supply.

- People who buy counterfeit opioid or benzo pharmaceuticals may be unaware of the risk of fentanyl adulteration and experience accidental overdose as a result.

Fentanyl may be intentionally mixed in with non-opioid drugs if someone makes a personal fentanyl-containing mixture for themselves, such as a speedball (mixture of a downer and an upper, like fentanyl and cocaine).

- It is very unlikely that any dealer would sell someone a speedball without advertising it as such.

Fentanyl may be unintentionally consumed if it’s present in drugs that are not opioids or benzos. This is generally thought to happen because of accidental cross-contamination in the drug supply chain.

- There’s no incentive to cut fentanyl into anything except for other depressants because fentanyl’s effects are sedating, not stimulating.

- Consuming fentanyl accidentally would be very noticeable and cannot result in immediate dependence/addiction, as is popularly (but falsely) claimed by sensationalist media articles.

- Addiction is a series of behaviors that exist within a pattern, not a sudden condition.

- Accidental consumption may occur if someone mistakenly sells a fentanyl-containing product instead of another drug (this has happened).

We are mostly concerned about fentanyl appearing in cocaine and counterfeit benzos as of summer 2022.

Drug-specific depressant overdose clues

It’s important to not lump all drugs together – that’s the whole point of this guide. Using drug-specific clues can help you get a better feel for what might be going on with someone.

- Ability to be briefly roused, followed by immediately attempting to go back to sleep (this may not happen if someone is experiencing severe alcohol poisoning)

- Sometimes a lingering smell of alcohol (a useful context clue)

- Incontinence (urinating)

- Vomit (more expected with alcohol than opioids)

- Note: Extensive vomiting can cause life-threatening dehydration

- Possession of drugs that are commonly adulterated with fentanyl, specifically:

- Pharmaceutical pills, namely opioids (like oxycodone) or benzos

- Bags of powder, or small squares of plastic wrap with powder residue on them

- As of late 2022, affiliated orgs in various regions have reported seeing GC/MS (lab) confirmed cases of meth and, much more rarely, MDMA contaminated with fentanyl

- Evidence of injection, such as paraphernalia (syringes, cookers), abscesses, or track marks

- Evidence of consuming pressed pills or powders via insufflation (snorting) or smoking

- Pinpoint (small) pupils

- It can be difficult to identify pinpoint pupils if you don’t have a medical background, so using this as a clue is typically not advised

Note: Opioid overdose sometimes can involve seizure-like activity, such as jerking, twitching, gurgling, or gasping. This can happen when the brain isn’t receiving enough oxygen. A person’s breathing rate is the biggest clue when it comes to opioid overdose.

- Known consumption of an opioid-like drug, mainly in regions east of the Mississippi River in the U.S. as of mid-2022, and a lack of full responsiveness to Narcan

-

- Xylaxine and benzodiazepines are potent central nervous system (CNS) depressants and can increase the depressant effects of other drugs, particularly opioids

- Do not speculate on this without having the relevant context clues about the person’s history of use and geographic location

- Xylazine can cause abscesses and skin necrosis in areas that are totally separate from an injection site (an unusual and specific clue), as well as other systemic health issues

Laypersons, in general, should not try to speculate about more complex adulterants like xylazine or benzos in opioids. Both of these trends happen in different regions and require specific knowledge and tools to identify. We’ve included them here to give an idea of just how complicated it can be to try to figure out what happened to someone without lab analysis.

“G” is a slang term that refers to GHB, 1,4-B, or GBL. 1,4-B and GBL are “prodrugs” for GHB, meaning that they get broken down into GHB in the body. While they ultimately have the same general effects, there are differences in dosage, duration, and specific risks. You can learn more about these differences here and here.

(Note: The typical dose of GHB is closer to 1.5 to 3.5 mL. The GHB dosage on the chart on our Instagram graphic is very conservative.)

- G-type drugs are very dose-sensitive. A few milliliters can make a huge difference in the effects.

- G-type drugs have a taste a bit like soapy baking soda that is easily concealed in alcohol. Alcohol is high-risk to mix with G because the effects of both are multiplied.

- Taking too much G is called getting “G’d-out.”

- G-type drugs can cause “micro-sleeps,” where someone goes in and out of sleep without realizing it, even while standing up.

- This can end up as a deep unconsciousness if someone is fully g’d out.

- Micro-sleeps can visually look a little bit like nodding on opioids.

- Getting g’d out can make someone sweat a lot, become clammy, slur their words, and otherwise act as though they’re extremely drunk.

The phrase “getting roofied” has become a general catch-all for being dosed without consent, but “roofies” actually refers to Rohypnol, which is a brand name benzodiazepine (similar to Xanax).

The specific effects of being dosed with a depressant like a benzo, a G-type drug, alcohol, a muscle relaxant like Soma, or something totally out of left field will vary – but look and feel pretty similar – depending on the substance in question.

Rather than saying “roofied,” which implies that a specific and rare drug was involved, a more accurate word is “dosed.”

When do I administer Narcan?

In party environments specifically, it’s much more likely that a depressant overdose is due to alcohol poisoning than fentanyl contamination. This being said: Fentanyl contamination is a significant concern in the U.S. right now. Accidentally consuming it can be fatal, and Narcan won’t hurt someone who isn’t overdosing on an opioid.

The guidelines for responding to an opioid overdose are slightly different if the person is known to have a physical dependency on opioids, which is outside of the scope of this guide.

Someone is still breathing, but very slowly (<7 breaths per minute). They’re unconscious or have severely reduced consciousness. They’re not responding to attempts to rouse.

Determining the course of action:

- In this situation, your priority is stabilizing the person’s breathing. This can be accomplished through:

- 1) Narcan administration (which will only be effective if there’s an opioid overdose taking place), or

- 2) other methods like rescue breaths, which you should only administer if you’re trained to do so.

- If you do not have a reason to suspect that the person uses opioids regularly, administering Narcan is a good move in this situation.

- If you suspect or know that the person might use opioids regularly, it is preferable to try to stabilize their breathing through rescue breaths before resorting to Narcan. (More explanation on this below.)

- In either case, make sure to monitor the person for signs that they’ve stopped breathing, at which point you’ll need to step in and administer CPR (see scenario 2).

- You can check their breath by holding your hand above their mouth and nose to feel for warm air.

If you administer Narcan:

- Turn the person on their side in the recovery position after administering Narcan. This will help prevent choking if they vomit.

- If the first dose of Narcan isn’t effective after about 2-3 minutes, you can try administering a second one.

IMPORTANT NOTE

If you know or suspect that someone uses opioids regularly enough to have a physical dependency, administering overdose reversal drugs like Narcan requires a bit more care.

- You only need to give someone enough Narcan to stabilize their breathing (ideally taking a breath every 5-ish seconds); they do not need to wake up fully.

- Large doses of overdose reversal agents can make someone violently ill – a state called precipitated withdrawal – if they’re physically dependent, which may be traumatic and cause them to avoid help in the future.

- Try to use the minimum viable amount of Narcan necessary whenever possible.

- If you do give someone enough Narcan that they wake up fully, and they have a physical dependency on opioids:

- Precipitated withdrawal can cause someone to wake up agitated or distressed, so stand back and give them room to acclimate to their environment.

- Be gentle with anyone who is emerging from a state of unconsciousness, overdose-related or not.

People who do not use opioids regularly are not at risk of precipitated withdrawal, even if they’re given a very large amount of Narcan.

Someone is not breathing at all. They’re unconscious and are not responding to attempts to rouse.

In this situation, your response will depend on whether 1) their heart has also fully stopped (they’re in cardiac arrest) or 2) they’re known or suspected to be a regular consumer of opioids.

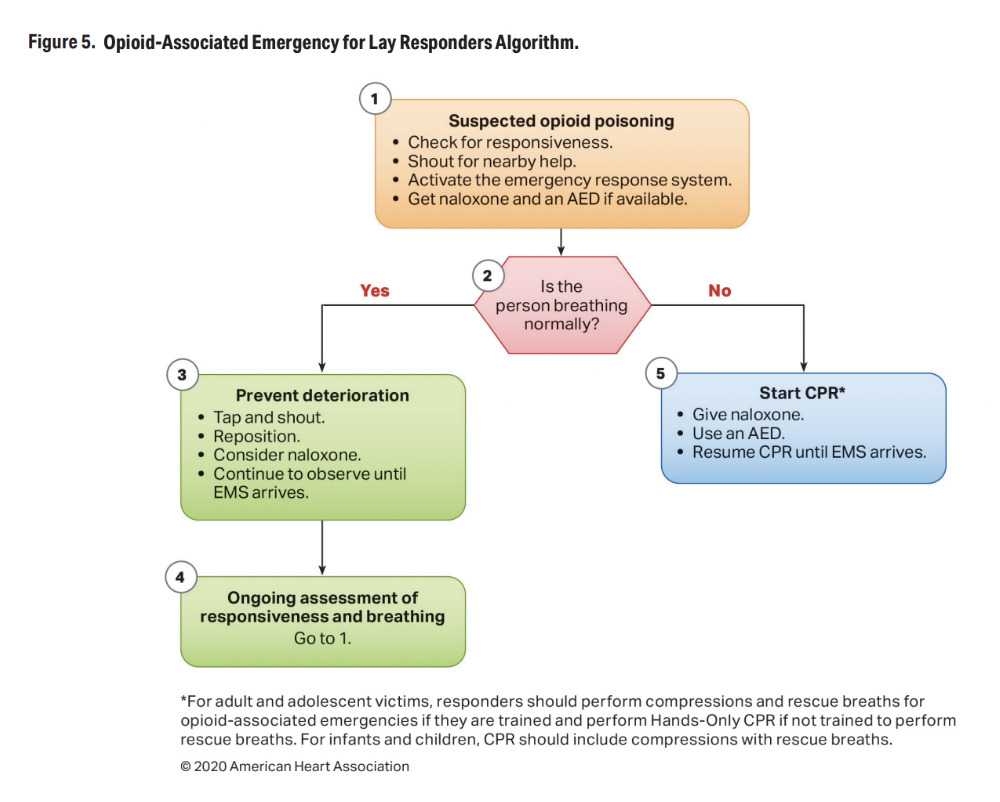

Why is 1) relevant? If someone’s heart has stopped fully, it means they’re in cardiac arrest. Narcan has limited efficacy for people who are already in cardiac arrest, so paramedics prioritize keeping blood circulating by doing chest compressions or using a defibrillator. Narcan can and should still be administered to someone who’s in cardiac arrest, if it’s readily available.

Why is 2) relevant? If someone consumes opioids regularly, using Narcan can put them into a very uncomfortable state of withdrawal. Supervised consumption sites and syringe exchanges typically prioritize rescue breathing to stabilize someone’s respiration and make sure their heart doesn’t stop fully.

- If their heart has fully stopped and they’re not breathing at all: the number one priority is starting CPR. Only attempt rescue breaths if you’ve been trained to do so. Incorrectly administering rescue breaths could waste precious seconds doing chest compressions.

- Administer Narcan if possible.

- Remember that you’re administering Narcan as a failsafe, and there are many unknowns in a situation like this. Refer to the rest of the guide to review the other reasons why someone might enter cardiac arrest.

- If their heart is still beating and they’re not breathing at all: the number one priority is administering Narcan and/or giving rescue breaths if you’re trained. The goal is to prevent their heart from stopping fully and entering cardiac arrest.

- If you don’t have Narcan on hand and someone is not breathing but their heart has not stopped, rescue breaths are the most important thing you can do. If their heart has stopped, full CPR (compressions and rescue breaths if you’re trained) is the most important thing you can do.

- If you know or suspect that someone uses opioids regularly, stabilizing their breathing through rescue breaths is preferable to giving them Narcan. It may be a long process, so be prepared to sit with them.

You’re not sure whether someone is breathing or in cardiac arrest. You’ve tried (and failed) to rouse them, but you don’t feel confident in your ability to tell whether they need CPR.

- Start by administering Narcan.

- Once you’ve done so, take a moment to get grounded before attempting to figure out whether the person might be in cardiac arrest. (This is why taking a CPR course is so important!)

- If you’re really not sure whether their heart is beating, start administering CPR.

Again: Administering Narcan to someone who is not experiencing an opioid overdose will not harm them. Always call for medics right away.

What if someone wakes up after Narcan?

Just because someone regains consciousness after being given Narcan does not confirm that they were overdosing on an opioid. There are far more Narcan administrations than there are actual overdoses.

It is still possible that an incident may have been caused by opioid overdose, especially given fentanyl’s increasing presence in cocaine, but this needs to either be:

- confirmed with hard facts, or

- stated as a possibility rather than a certainty.

In most party settings, it is more likely that a person’s unconsciousness was the result of environmental/circumstantial factors than opioid overdose, even if they woke up after Narcan.

Someone’s unrelated loss of consciousness might be mistaken for a fentanyl overdose because:

- People may briefly lose consciousness and coincidentally wake up after Narcan is administered, making it look as though they’d experienced an overdose reversal.

- People may regain consciousness in response to the pain stimulus of being injected with Narcan, or the stimulation of having it sprayed into their nose.

- People may lose consciousness due to panic at the possibility of experiencing an opioid overdose, and recover due to the placebo effect of having an antidote administered. (This is very common.)

- People may experience cardiac arrest following a complication such as stimulant overdose (overamping) and require CPR, which is often co-administered with Narcan.

- Note: Many pressed pills containing novel cathinones (or other novel stimulants) are dosed dangerously high, which can lead to life-threatening overheating, rhabdomyolysis, arrhythmia, and sometimes cardiac arrest.

**Event medical teams have recently started widely administering Narcan to people who are unconscious as a better-safe-than-sorry measure, even if there isn’t enough information to determine whether opioid overdose is likely. Witnessing EMS administer Narcan is not evidence that someone overdosed on an opioid.

Recap

In the context of depressant overdose, there are three main things to consider when you’re responding to a loss of consciousness:

- Are they breathing? If so, are they breathing less than 7 times per minute (once every 8 seconds or so)?

- Is their heart beating (are they in cardiac arrest)?

- Do you know or suspect that they use opioids on a regular basis?

Depending on which of these things are taking place – or not – your response will be slightly different.

When talking about what happened, remember:

- Responding to Narcan is NOT a guarantee that fentanyl (or another opioid) was involved.

- Even if the situation was an opioid overdose, there are dozens, if not hundreds, of novel and prescription opioids on the market. Fentanyl is not the only opioid out there.

- Semantics matter. Fentanyl cannot be used as a catch-all for every negative experience related to drug use.

- Making assumptions about what happened to someone spreads rumors and misinformation. This makes it much harder to figure out what actually happened.

To confirm that someone actually experienced an opioid overdose, additional testing is needed. Two of the most important pieces of confirmatory evidence are:

- Toxicology reports on biological samples collected from the person in question (the results of toxicology tests are often HIPAA protected);

- or, more practically, lab testing of the materials ingested or remnants of the substance(s) consumed.

- Fentanyl test strips can provide additional information, but drug checking professionals must confirm that the strips were used correctly for a result to be validated.

- Only a lab with advanced drug checking technology like GC/MS can provide confirmatory evidence about what drugs are in a sample. Reagents and handheld field devices (like the ones cops use) are not sufficient.

As far as we’re aware, no testing has ever been produced to confirm the accuracy of reported fentanyl overdoses at events. (We have, however, received confirmatory evidence disproving reports of fentanyl overdoses at events.) This means that all claims thus far are speculation with varying degrees of confidence.

This doesn’t mean that it’s not happening. The risk is VERY real. Panic, however, has led to spades of reports of overdoses at events that are almost certainly not related to opioids at all. Some of the reports are downright outrageous and cause significant harm to our community. Confirmatory testing is very difficult to come by, making it impossible to truly know how many of these reports are legitimate.

Problems arise when speculation – even educated speculation – is conveyed to law enforcement, security, or the general public as being fact, without acknowledgment of the limitations of what can be determined on-site. (Again: See this article for more information.)

This is all very complex. Confirming an actual fentanyl-related opioid overdose at an event is a specific differential that would need to rule out dozens of other opioids, many different circumstances, medical anomalies, and environmental factors. It requires a much higher level of recreational drug specialization than almost any event staff typically have, including EMTs (and especially law enforcement).

Right now, most people have no idea what’s real and what’s rumor. This is a huge problem because it degrades trust in public health figures and makes it impossible for people to prepare themselves for what is actually taking place. We waste an enormous amount of resources on wild goose chases because speculation is communicated as fact.

Giving Narcan to people who are obviously not experiencing opioid overdose is wasteful and may have consequences, in rare cases. Chronic pain patients who take opioids regularly, for example, could experience withdrawal if they’re given Narcan needlessly. It won’t harm them, but this is one example of why it’s important to know the actual signs of opioid overdose, rather than giving someone Narcan if they experience any sort of discomfort or anxiety.

If we’re going to restore people’s trust in health authorities, we need to be able to speak honestly about the limitations of what we know.

Heat-related Illness

Heat-related illness includes heatstroke, heat exhaustion, and heat syncope (fainting). Each of these is characterized by varying degrees of overheating.

Heat-related fainting often happens because of blood pooling in the legs and rushing to the skin, which reduces blood flow to the brain. Not everyone who has a heat-related emergency will pass out, but passing out in the heat is common!

- Severe overheating (>104º) can damage organs and cause coma.

- Dehydration, sun exposure, lack of airflow, hot environments, and physical exertion all speed up the process of overheating.

- Heat is the number one cause of MDMA-related medical emergencies.

- Heat illness – especially dehydration or even over-hydration – can make you feel very unwell, to the point of causing full-blown panic attacks.

- Many well-intentioned bystanders have mistaken panic attacks for fentanyl overdoses (or nonconsensual dosing) even though the symptoms look totally different.

Identified by:

Seizure

Seizures are caused by erratic electrical signaling in the brain. This can happen because of certain medical conditions, overstimulation, and/or certain substances taken under specific circumstances. Syncope and seizure can sometimes be difficult to tell apart without medical training.

Identified by:

- Normal/fast breathing and heart rate

- Sudden onset OR preceded by “prodrome” for hours or days

- 30 second to 5 minute duration – 5+ minutes OR multiple seizures in a row is an emergency

- Physical signs that vary from person to person

- Often triggered by overstimulating experiences

- Everyone should know seizure first aid.

- Do not try to put anything in someone’s mouth when responding to a seizure.

- Set a timer when the seizure starts. Any seizure lasting over five minutes requires emergency treatment.

- Anyone can have a seizure, with or without epilepsy. Many people do at some point in their lives.

- Head injuries sometimes happen when someone falls during a seizure. This can make the postictal (post-seizure) state appear even more like an altered state.

- Seizures can happen when a person is generally overwhelmed, even if they don’t have epilepsy.

- This is common when someone:

- has taken a drug that may lower their seizure threshold (like Tramadol)

- has combined multiple drugs that can cause seizures when used together (like combining classical psychedelics and lithium)

- has taken a drug that increases sensory stimulation, and then entered a very stimulating environment (like doing cocaine in a crowd at a festival)

- has experienced strong, sudden fear

- any of the above, plus having an intense emotional experience.

- This is common when someone:

Don’t speculate on the cause of a seizure, or try to confirm that you are 100% right in diagnosing one. Syncope and seizures can look very similar, even to medical professionals. Convey only observations about what you have seen.

Syncope

Syncope – which is, in essence, fainting – has various causes, including dehydration, heat, stress, hyperventilation from anxiety/panic, etc. People sometimes pee themselves in a syncopal episode and might wake up confused, disoriented, or fearful. Syncope is often prefaced by a general feeling of being extremely unwell or even on the brink of death, especially if it’s brought on by panic.

Syncope is caused by sudden changes in blood flow, which can be triggered by psychological responses such as stress, overexcitement, or overstimulation in addition to environmental factors. Some people undergo syncope when standing up too quickly, getting blood drawn, or experiencing strong fear that their safety is at risk. Being dehydrated, tired, and underfed all significantly increase the risk of syncope, especially when there is a strong precipitating emotional event.

An example of this is the recent flurry of tabloid articles about “injection drug attacks.” Widespread fear around being jabbed has led to an uptick in panic-related syncope at events when people feel pricks and pokes in the crowd.

- We released an article evaluating the validity of injection drug attacks and debunking the likelihood that they’re actually happening.

- As a brief example, feeling “a pinch” and then feeling unwell or sick within seconds is not indicative of an injection attack.

All of the reports we have received about injection attacks have come from individuals who were already vigilant about them, and all reports have been deemed contextually unlikely after we discussed what happened.

Identified by:

- Normal/fast breathing and heart rate

- Pins and needles

- (Sometimes) feeling like something is terribly wrong

- Loss of consciousness lasts under a minute or two

- Fairly fast (or very abrupt) loss of consciousness

- Sometimes a “prodrome” of feeling very sick or “off,” like something is very wrong physically. There might be no obvious reason why.

- This tends to be extremely unpleasant and often brings on a panic attack, which can feel like a life-threatening medical emergency.

- People don’t always pass out after this prodrome stage. Feelings of clamminess, dizziness, fast heart rate, and cold sweats may continue for up to 20 or 30 minutes and may or may not culminate in vomiting, defecating, or passing out fully.

- It is common for people to mistake panic attacks for opioid overdose because there’s no obvious cause for why their body feels unwell, but people who are actively overdosing on opioids do not realize it and cannot Narcan themselves. The symptoms of syncope do not match those of opioid overdose.

- Some people have specific disorders, like vasovagal syncope or other orthostatic hypotension disorders, that make them more prone to syncope.

- People with low blood pressure are at higher risk of syncope.

- Tingling or pins and needles in various body parts, commonly the hands and face.

- This is due to hyperventilation, which is a subconscious part of the body’s fight or flight mechanism.

- Hyperventilation is intended to bring more oxygen to your muscles so you can run from a predator, but if you’re not in actual danger (or running) it can make it feel like your skin is vibrating.

Syncope may have a gradual lead-up (“prodrome”) of feeling like something is increasingly wrong, or it can happen very abruptly. A sudden loss of consciousness without prior warning is almost always due to syncope, seizure, head injury, or some acute drug-related response like “fishing out” on nitrous.

- Passing out for under a minute or two before regaining consciousness.

- Sometimes the person may twitch and spasm while they are unconscious. This does not necessarily mean they are having a seizure.

- A seizure is followed by disorientation and/or a feeling of being unwell for a few minutes or, less commonly, a few hours.

- Syncope takes only a few minutes to recover from, although it can be psychologically jarring and put a person on edge as they constantly evaluate their body for signs of another attack.

- It can take even longer to recover from syncope if the original cause – like dehydration, exhaustion, or lack of food – isn’t addressed.

- Sometimes the person may twitch and spasm while they are unconscious. This does not necessarily mean they are having a seizure.

- Normal or fast breathing/heart rate during and prior to loss of consciousness.

This is an immediate indicator that someone is NOT experiencing opioid overdose, which is characterized by very slow breathing.

Head Injury

Head injuries are caused by a blow to the head like elbowing in a crowd, falling, etc. Head injuries can present as altered states and may be difficult to differentiate from drug-induced symptoms, particularly when the injury is severe and someone is unconscious, also on drugs, or unable to explain/remember what happened to them. Many people have incurred head injuries after falling while having a seizure or doing nitrous standing up.

Identified by:

- Physical symptoms like headache, lack of coordination, nausea/vomiting, blurred vision, or loss of consciousness in severe cases

- Mental symptoms like confusion, irritability, or in severe cases seizures or slurred speech

- Guide to signs of concussion and TBI (traumatic brain injury)

Cardiac Arrest

Cardiac arrest occurs when the heart stops beating, and has many causes. Cardiac arrest is an electrical problem, while heart attack (a different condition) is a circulatory problem.

Cardiac arrest can occur as a result of tachycardia (fast heartbeat), but more often occurs as a result of bradycardia (slow heartbeat) or arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat). It is possible for someone to enter cardiac arrest because of overamping on a stimulant.

Cardiac arrest can also occur as a result of prolonged oxygen deprivation, electrocution, pre-existing heart conditions, or even very strong emotions, which can trigger severe arrhythmia.

Identified by:

- Absent pulse

- Blue or gray tinting to extremities, as a result of oxygen deprivation due to the heart not beating

- “Agonal breathing,” a gasping, choking sound that indicates that the body is not breathing

- Guide to recognizing and responding to cardiac arrest

THERE ARE MANY ADDITIONAL REASONS WHY SOMEONE MIGHT LOSE CONSCIOUSNESS. LOSS OF CONSCIOUSNESS CAN BE BRIEF OR PROLONGED, SUDDEN OR GRADUAL, AND DUE TO COUNTLESS THINGS.

How to respond

Try to rouse the person.

You can gently press on their shoulders, clap, and yell “hey there, can you hear me?” to attempt to wake them. If this doesn’t work, use commands like “open your eyes” or “sit up.”

- If they still don’t respond, you can try saying something alarming that would usually stir them – “There’s a fire!” or “Your mom is here!”.

- Pain stimuli:

- Pain stimuli are methods that can be used to attempt to wake someone if they’re not responding to other cues.

- People sometimes move their arms and scrunch up their face in response to pain stimuli, but this can be an automatic reaction and doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re awake.

- If they don’t open their eyes, talk to you, or try to push you away, consider them to still be unconscious until/unless they do.

- The easiest pain stimuli involve pinching the inside of someone’s arm or thigh, their earlobe, or their nail bed.

Collect information about what’s happening.

Look for friends nearby.

- Having clues about what happened to a person can help you figure out what to do next.

- Friends (or people who witnessed someone passing out) can provide information about when, how, and why it might have happened, helping you create a timeline. They can also help move the person if needed or call for assistance.

- Friends can sometimes give you/medics information about any medical conditions a person has, any medications they’re taking, any drugs they’ve consumed, and what their behaviors have been like throughout the day.

Observe the symptoms the person is exhibiting.

Are they stirring at all? Making any noises? Have they urinated or vomited? Are they jerking or spasming? How fast or slow are their breathing and heart rate?

- Try to write down all of the information you collect, especially the timeline of their loss of consciousness, specific symptoms that the person exhibited before, during, and after losing consciousness, and any other context clues.

- Have this information ready to show medics when they arrive. It’s very important to erase any sensitive information about their health conditions and medications immediately thereafter.

If someone is unconscious, doesn’t wake up quickly, and has a very slow or stopped heart rate/breathing:

Call for help (911, festival medics).

Look around for an on-site/public automated defibrillator.

- Send someone to get help and/or point to someone to call 911. Be specific, don’t just shout “someone call 911,” and do not leave the person alone while getting help.

- You can read about state-by-state Good Samaritan laws here.

- Police alternatives can be found here.

- Ask the 911 operator for medics only. Say that someone is not breathing and is unresponsive. Medics should arrive with Narcan regardless of whether you mention the possible involvement of drugs, but if you’re worried you can explicitly request that the ambulance bring Narcan just in case.

- Be aware that doing so may bring unwanted law enforcement presence to your location.

- Remove any drugs from your person and attempt to remove them from the person who’s unconscious as well.

- Take note of anything you find, as it may provide essential clues as to what happened.

Check their airway for any obstructions like food or vomit.

This may prevent them from breathing on their own. Clear the airway if it’s obstructed.

Administer CPR if they’re not breathing and their heart has stopped. Administer rescue breaths (and Narcan, just in case) if they’re not breathing but their heart is beating.

Correctly administering CPR sometimes breaks ribs.

See section two of “when do I administer Narcan?” for more information on exactly what circumstances require Narcan, chest compressions, and/or rescue breaths. Be trained to give all three so you’re ready in the worst case scenario.

If someone is unconscious, but breathing:

Monitor the speed and depth of their breathing.

If either is normal or fast, the person is not experiencing opioid/depressant overdose.

- If a person doesn’t have slowed breathing, the loss of consciousness is likely because of something else.

- If you’re not sure, administer Narcan anyway and put them in the recovery position.

- Other depressants can also cause a person’s breathing and pulse to be shallow and slow, like alcohol and benzos (ketamine does not decrease heart rate on its own, and may actually increase it).

- This is especially important when someone has mixed multiple depressants.

Evaluate the person’s physical state.

All of the following symptoms merit calling for medical attention and taking action.

- Overheating:

- Usually characterized by hot/flushed skin and sweating.

- If someone is in a serious heat stroke state, they won’t be sweating anymore. This article contains information about responding to heat injury.

- Remember that the most effective cooling places on someone’s body are their wrists, the back of their neck, under their arms, and their inner thigh crease area, where blood vessels are closest to the surface.

- Vomit or urine:

- If someone has already vomited or peed themselves and it’s visible on their clothes or person, they might be dehydrated from loss of fluids. This is a good indicator that they should receive medical attention in case they’re:

- dehydrated, or

- at risk of vomiting again and choking on it. (Put the person in the recovery position to avoid this.)

- If someone has already vomited or peed themselves and it’s visible on their clothes or person, they might be dehydrated from loss of fluids. This is a good indicator that they should receive medical attention in case they’re:

- Shivering or convulsing:

- This can be a sign of many things, depending on the weather and environment. Sometimes shivering is obviously due to cold, but other times it can be a paradoxical effect of heat injury.

- Convulsing can also occur as a result of some pre-existing medical conditions, taking certain drugs, having a seizure, experiencing syncope, experiencing intense emotions, going in and out of sleep, or entering into a heat stroke state that causes muscle breakdown.

- Obvious injuries:

- Any head injuries should be evaluated by medical professionals in case of concussion, especially if followed by more serious symptoms like persistent severe headache, intense mood swings, disorientation, or loss of coordination.

If the person doesn’t seem like they’re at particular risk for any of the above, proceed to the following.

- Open their mouth and check their airway for vomit or obstruction. Clear the airway if it’s obstructed. (People sometimes wake up during this part.)

- Roll the person on to their left side in the recovery position. This will help keep their airway open if they vomit.

Next steps will largely depend on context and circumstance.

- If you’re at a festival or other event with medics present, call for medics.

- The person may be dehydrated or experiencing something that later requires medical attention.

- If you are not in a position where medics are available, monitor the person’s condition for 15-30 minutes to ensure it doesn’t worsen.

- People who don’t exhibit any concerning attributes of the Status Check above will probably not need much more than some time and space to recover.

- If the person is occasionally waking up, swatting you or mumbling, and going back to sleep (usually because they’re very drunk), there is not likely significant immediate danger and you’re probably not going to be able to do much. Try to leave some water with them.

- The biggest thing here is usually the risk of choking on vomit, which is why it’s so important to monitor people who have passed out.

- If someone is at risk of becoming very hot or cold, very dehydrated, sunburned, stepped on, or otherwise harmed, you should do your best to try and remedy those things before walking away. Ideally locate staff or friends who can take over monitoring their condition.

Do not leave someone alone who is in an unsafe location or whose condition isn’t clear. You can ask a friend or even a stranger to help out by going to fetch medical while you stay with the person.

On your own

Take a first aid/CPR course. This can easily save someone’s life (or at least their night). This knowledge is incredibly important.

You can find Narcan using the Harm Reduction Coalition’s naloxone finder.

You can check your state’s laws around Narcan acquisition here.

These are useful for rescue breaths. Lack of oxygen over the course of four minutes can lead to permanent brain damage.

CPR masks act as barriers to reduce the risk of communicable diseases when performing rescue breaths.

Note: It’s not uncommon to accidentally feel your own pulse, or not be able to find the pulse. Don’t waste time on this if someone collapses and is not responding or breathing – call for help immediately.

- The American Heart Association doesn’t prioritize teaching laypersons how to check pulses because it takes up time that could have been spent on CPR.

You should put a person in this position if they have a pulse and are breathing, but unconscious. It prevents them from choking (if they vomit) and blocking their own airway with their tongue.

This can be very useful if you see someone doing something harmful to someone who is seizing, like trying to put something in their mouth.

- Step-by-step first responder’s guide on responding to overdose.

- Guide to responding to various types of unconsciousness.

This includes the recovery position, which is an essential piece of first aid information that everyone should know.

Big takeaways

- Just because someone woke up in response to Narcan does not necessarily mean they were experiencing an opioid overdose.

- Case in point: law enforcement officers who claim to have been revived by Narcan, but whose lab work found no opioids.

- Just because someone needed CPR does not necessarily mean they were experiencing an opioid overdose.

- Cardiac arrest can occur for many reasons. It will not hurt someone to administer Narcan anyway, but don’t jump to conclusions about whether cardiac arrest was due to overdose.

- Just because someone has passed out doesn’t mean they’re not breathing.

- It’s very common for people to lose consciousness but continue breathing normally. Check their breathing before making assumptions.

- If you’re not sure, step in.

- You might mess up, give someone Narcan who doesn’t need it, or start chest compressions on someone who has a pulse. It’s way better to make mistakes than to not act.

It’s okay to not be sure why something is happening.

The most important thing is that you’re honest about the limitations of what you know, straightforward about your observations of a person’s symptoms, and mindful about how your language can misrepresent a situation.

Even medical professionals and law enforcement officers are not drug experts by training. Emergency medical services are NOT drug checking or drug science experts. EMS can sometimes unintentionally spread misinformation because of this lack of expertise, or even because of internalized biases.

Being in emergency response gives a platform and position of power when speaking on health matters, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that the person behind the statements is correct.

Without actual confirmatory proof, many things in medicine are educated speculation. It’s important to use neutral language to reflect this reality; negative or biased language has the potential to do more harm than good.

Be safe out there,

DanceSafe