Community Responses to Sexual Violence

Last Updated: August 15, 2023

CW – Rape and Sexual Assault, Drug Facilitated Sexual Assault, Abuse

Written By: Sloane Ferenchak, WeLoveConsent Contractor; Edited by: Kristin Karas, Director of Operations, DanceSafe & Stacey Forrester, Goodnight Out Vancouver

WeLoveConsent seeks to help dismantle rape culture and build a consent culture within the electronic music and nightlife communities. WeLoveConsent initiatives and services focus on mobilizing the community to build a consent culture and reduce the incidence of sexual violence in nightlife settings through consent education and bystander intervention.

Datsik wasn’t the first, and unfortunately isn’t the last, artist in the electronic music and nightlife communities to fail to demonstrate the principles of consent culture. If you’ve tuned in to your social media feeds the past few weeks/months, you know that several artists and DJs have been accused of perpetrating sexual violence, some not for the first time: Space Jesus, Nahko, Bassnectar, Snails, Thriftworks, and Graves.

DanceSafe promotes the health and safety of the electronic music and nightlife communities: we do not condone sexual violence of any kind. While we aim to promote a consent culture by meeting community members where they are with the understanding that we all have interacted with, and likely perpetuated rape culture in some way, we also recognize the importance of maintaining community safety. Due to the repeated nature of the allegations and his subsequent lack of accountability, it is evident that Space Jesus, as well as the other named artists, have a lot of work to do on their own before they can help dismantle rape culture and create a consent culture in its place. Thus, WeLoveConsent’s relationship with Space Jesus has been terminated.

As we’ve discussed in our statement on Datsik, how we respond to allegations of sexual violence as individuals and as a community can perpetuate, or dismantle, rape culture. If we want to keep our community a safe place for connection, it is pertinent to look at how power dynamics play into artist sexual misconduct, and how ownership and accountability are necessary to address and repair consent violations. We need to think critically about what it means to be called out for our mistakes by our community, and what to do when this happens. We also need to think about how, as a community, we can balance educating one another, holding each other accountable, and keeping each other safe.

A Common Thread: Power Dynamics, Consent, and Sexual Violence

Back to back sexual violence allegations have left the music community shaken as reports of older men abusing their position of power in relationship to (often younger) femme identified fans have surfaced. How could so many DJs be named as perpetrators of behavior that violates the spirit of our community that promotes love, unity, and respect?

First, we need to recognize that we live in a society full of power structures which inherently privilege some and marginalize others based on their socioeconomic status, job, race, gender, disability, sexuality and other social positions. Individuals at the top of the system hold more power and influence as a result of their privilege. Unfortunately, those at the bottom of the system have fewer resources, less power, and often are taken advantage of by those in higher positions of power within the structure.

Power dynamics are how people interact when differences in access to power, authority, and influence are at play within any relationship. Power dynamics certainly play out with groups as well with individuals. Power isn’t inherently good or bad, but a person with a privileged social position may have more social credibility and influence that could be used to take advantage of others. People with power may also not be aware of how their actions negatively impact or influence the decision making of “less powerful” people. For example, when there is a power imbalance in a sexual interaction, a person with “less power” may feel anxious, uncomfortable with, or unable to say no. They may fear social rejection, losing their economic or social position, or experiencing violence if they do not do what the person with power or authority tells them to do. They may feel like they have no power to speak up, be truly heard, or get justice.

When someone feels like they can’t say “no,” their consent is not freely given. When they are manipulated, their consent is not informed. And when an individual feels pressured to do something they don’t want to do, their consent is not enthusiastic.

Music artists tend to hold higher positions of power in our community that may be layered on top of other privileged identities (e.g. cis-gender, male, white or white-passing, wealthy, etc.). While anyone can perpetuate sexual violence, holding more power and privilege can increase the risk of abuse of power, both intentionally and unintentionally. Most, if not all, of the current accused artists have been cis-identified males, and the targets of their misconduct have tended to be (often younger) femme presenting or identified people. Accounts of many of the survivors mention being taken advantage of when high, and some mentioned being drugged (see this toolbox blog for information on substance use and consent). In all cases, a power differential was present which put fans at a higher risk of being taken advantage of by these artists. Even if they “enthusiastically” consented, their lack of experience and power made informed and freely given consent more difficult to establish, and frankly, less likely, given the nature of rape culture that permeates our society.

Ownership & Accountability

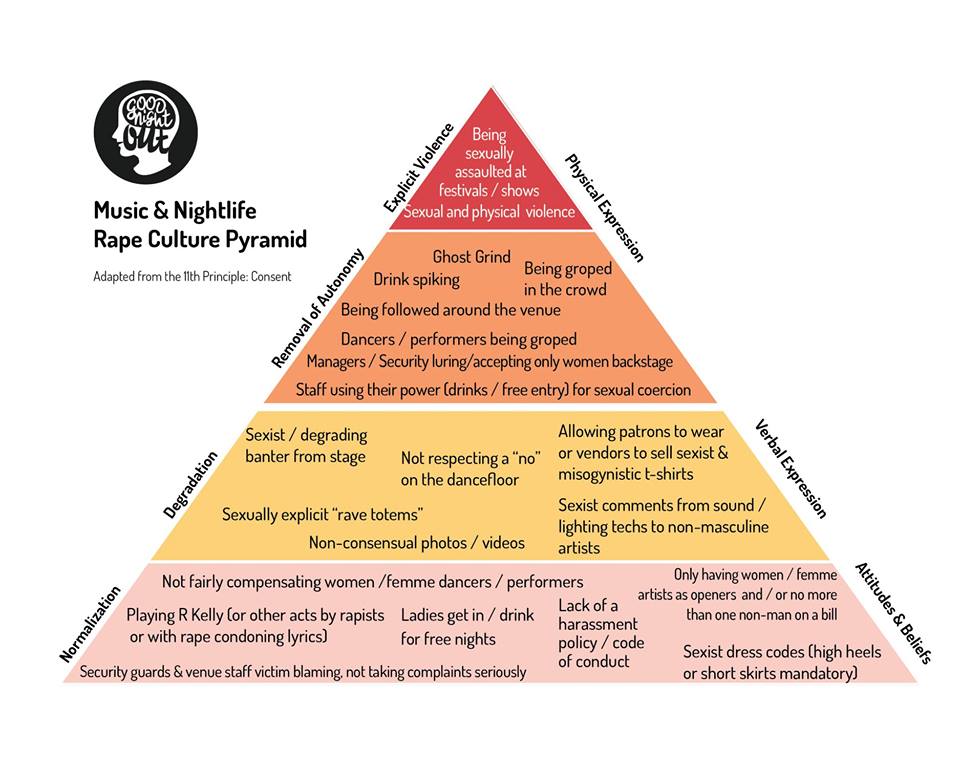

We all are influenced by rape culture, and although we may not all be festival headliners, we have all at some point perpetuated it, even if in a subtle, nuanced way (see graphic below). When it happens, it is important for us to examine our intent, the impact of our behavior, and how we should respond to heal some of the harm we have caused. In order to grow from our mistakes, we need to be able to acknowledge and reflect on our contributions to them. The same goes for the artists that we love in our community. Most of the artists listed in this article released statements in response to the accusations against them. While some were better than others, none of these responses demonstrated adequate ownership or accountability, despite multiple references to both.

What is Ownership?

What is Ownership?

Ownership of a mistake and the harm caused is necessary to begin the process of making amends and growing. It involves recognizing that you’ve hurt someone and taking personal responsibility for your mistakes, rather than denying them, making excuses for them, or placing the blame elsewhere. It involves understanding what you’ve done, challenging your own behavior, and making a personal commitment to resolve the violation within the boundaries of those directly harmed.

Ownership isn’t guided by what we think others expect of us to save our career and avoid being a social pariah; it comes from the internal motivation to want to be better. Ownership doesn’t mean that you can’t get help from others, but that you are responsible for your own initiative. As leaders, DJs have extra responsibility to own the ways they have perpetuated harm in the electronic music and nightlife communities, and listen to what their community (especially survivors) has to say about what to do about it. Denying ever having done something without consent, failing to own your responsibility in the hurt caused, and placing blame on the person hurt is not ownership.

What is Accountability?

If we think of ownership as the initiative to do what is needed to make things right, we can think of accountability as follow-through and transparency. Accountability involves taking the necessary steps to repair damage based on what those harmed feel is needed and taking personal responsibility for the result. To be accountable is to be transparent with the community about what active steps you are taking to right wrongs. Unfortunately, perpetrators of sexual violence often promise to be available to the community but fail to answer questions or provide detailed responses about what work they are doing. While you don’t need all the answers to be accountable, you need to actively be making steps towards the solution and be open to feedback your community and individuals harmed provide.

Community Response: Idolization, Call Outs, Call Ins, and Cancel Culture

In response to the string of sexual harassment, misconduct, and assault allegations against artists, survivors, consent advocates, and fans have spoken out in a variety of ways. While some people defend their favorite artists, others called out the problematic behaviors of these DJs and demanded accountability in various forms ranging from calls for restorative justice processes to full blown cancellation. To understand the reasons for and uses of these responses, let’s examine idolization, calling out, calling in, and cancelling.

The Impacts of Idolization

As a community, we admire, and sometimes idolize, the artists behind the music we love. When we idolize artists, we lose sight of their complexity. We may feel defensive and/or hurt when they don’t live up to our standards, and we may feel the urge to defend them or victim blame survivors. Idolizing artists instead of viewing them as our peers means we give them power which they can abuse, and ultimately idolizing artists can leave supporters feeling unheard and unsupported. While we may be mourning the loss of who we thought our favorite artists were, we must still center the experiences and needs of those coming forward about their negative experiences. We need to maintain standards for our behavior and those in our community, while also holding and understanding that people can change and work towards restorative justice.

Call Outs and Call Ins

When you are aware that someone has been harmful, one of the responses you may have is to “call them out” for their behavior. “Call outs” are statements that point out another person’s oppressive actions to the public. This serves two purposes: to make the person aware of their problematic behavior and to educate others. Ericka Hart, racial/social/gender justice activist and sex educator, explains that call outs begin “the process of accountability” and maintain transparency in the community. Call-outs are survivor-centered, which means that they should be based on the perspective of those harmed, and come from a place of love, including when pain is expressed.The more people who know what has occurred and why it was wrong, the more people who will hold the perpetrators accountable. The ultimate goal of a call out is to get someone to own, and stop, their problematic behavior. Call outs are a way for people to voice demands for change, and while they provide people opportunities to do better, they also hold the perpetrators accountable when they fail to put in the work needed.

We want to offer a way of responding which is different than how the accused artists have responded.

- When called out, it’s normal to initially feel defensive, but we should try to pause and reflect before responding.

- Assume call outs come from a good place, and work to humbly listen to them. Calling-out can cross lines when it intensely shames unintentional behavior, and anger may be hard to receive, but these responses often stem from very valid hurt feelings. While we may believe strongly in our view of the truth, this does not always match someone else’s experience, and we should do our best to listen.

- Be curious about the impact and how you contributed, and reflect on ways you can cease causing harm. Rather than think “I have never violated anyone’s consent before,” try to think, “I don’t want to violate anyone’s consent, but someone has been hurt by my actions. How can I gain more understanding so I don’t violate consent in the future? What can I do to make this right?”

Call ins are similar to call outs, but they have a slightly different approach and audience. While both aim to get someone to stop problematic behavior, call ins tend to use a more gentle approach to pull someone in. Call ins assume a person is capable of change if met with empathy where they are in their understanding. When performing a call in, it can require some privilege or distance from the experience of harm due to the emotional labor required to call in. With this said, a call in doesn’t mean repressing emotions in response to the person’s behaviors; when someone calls another person in, they honor their feelings while working to respond in a compassionate manner. If you are called out or called in, be thankful that someone took the time to educate and correct you; to hold another person accountable is a form of love.

Cancel Culture and Cancelling

Cancel culture has been a hot topic of debate in the past few years. When someone is cancelled, they are essentially boycotted. Anne Charity Hudley, the chair of linguistics of African America for the University of California Santa Barbara explains that the term comes from black culture, where it has been used to protest harmful ideals by refusing to participate in them. It can be a way to take power back from people with elevated social and financial status when you refuse to support their career. Cancel culture centers the safety of those harmed, especially when perpetrators haven’t shown ownership or accountability for harms they have caused. Canceling can send a strong message that certain behaviors are unacceptable in a community when change doesn’t feel likely or when too much pain has been caused.

With this said, cancel culture can go too far when taken to extremes, according to Loretta Ross, expert on race, women’s issues, and human rights. When someone is immediately cancelled for a learnable mistake, they may feel alienated and are less likely to do the work to make change. Some people may feel like they need to avoid difficult conversations to prevent being cancelled. Others may cancel people without ever engaging others in a way that helps them learn. Before you cancel, consider your position of power and privilege; will it be too much emotional labor to try educating someone first? Has the person shown potential for ownership and accountability, or has begun the process? If so, think about using a call out or call in method. Consider whether or not this person is a repeat offender and how much damage has been caused; sometimes cancelling is what is best for the safety of those harmed and the community as a whole.

Accountability as a Community

Many of us may be in mourning about what feels like a loss of connection and good vibes tethered to these artists, but this doesn’t need to be a total loss if we can maximize the safety of all community members. As an organization, DanceSafe is committed to helping this process by addressing harmful behaviors in our community and beginning a dialogue about community accountability. According to INCITE!, this process is when a community comes together to affirm anti-oppressive values and practices, provide safety and support of targeted members and their autonomy, encourage accountability, create strategies to address abusive behaviors, and empower members to oppose oppression and violence.

While it’s true that the only person responsible for committing sexual violence is a perpetrator, we all have the ability to look out for each other’s safety and combat rape culture in the electronic music and nightlife communities. We encourage our community to recognize this blog content as an invitation to examine how power plays into sexual interactions, and learn the processes of ownership and accountability as individuals and a community. This response from WeLoveConsent is just the beginning of a long conversation; look out for upcoming articles for exploring accountability strategies to address sexual violence in our community. We hope you will join us in our work to ensure our community remains a safe haven when we can all return to the scene.