IMPORTANT: Reagent Reaction Updates

Last Updated: December 15, 2023

By: Rachel Clark, Education Manager

DanceSafe National has determined that several reagent reactions on the DanceSafe color chart are no longer accurate, specifically those listed for cocaine, MDA, 2C-B, and oxycodone.

Background: We’ve spent the last several months conducting an internal review process of our existing color reactions to verify their accuracy. As part of this process, dozens of documents were created to track expected color ranges of possible reagent reactions for each major substance on our color chart.

These documents were formed by scraping the entire DrugsData database since its inception, evaluating reagent reactions for each substance as well as submissions containing adulterants (which may interfere with reagent reactions). The relevant documents have been linked in each section below. Documents include photo examples of the range of expected color changes for each substance and reagent.

We have compiled reagent results for every available combination and permutation of cocaine and the active impurities or cuts most commonly found alongside it. This includes:

- Cocaine, benzoylecgonine, methylecgonidine, tropacocaine

- Cocaine, methylecgonidine

- Cocaine, methylecgonidine, lidocaine, tropacocaine

- Cocaine, methylecgonidine, tropacocaine

- Cocaine, benzoylecgonine, methylecgonidine

- Cocaine, methylecgonidine, levamisole

- Cocaine, methylecgonidine, tropacocaine

- Cocaine, phenacetin, methylecgonidine

- Lidocaine, cocaine, methylecgonidine, procaine, tropacocaine

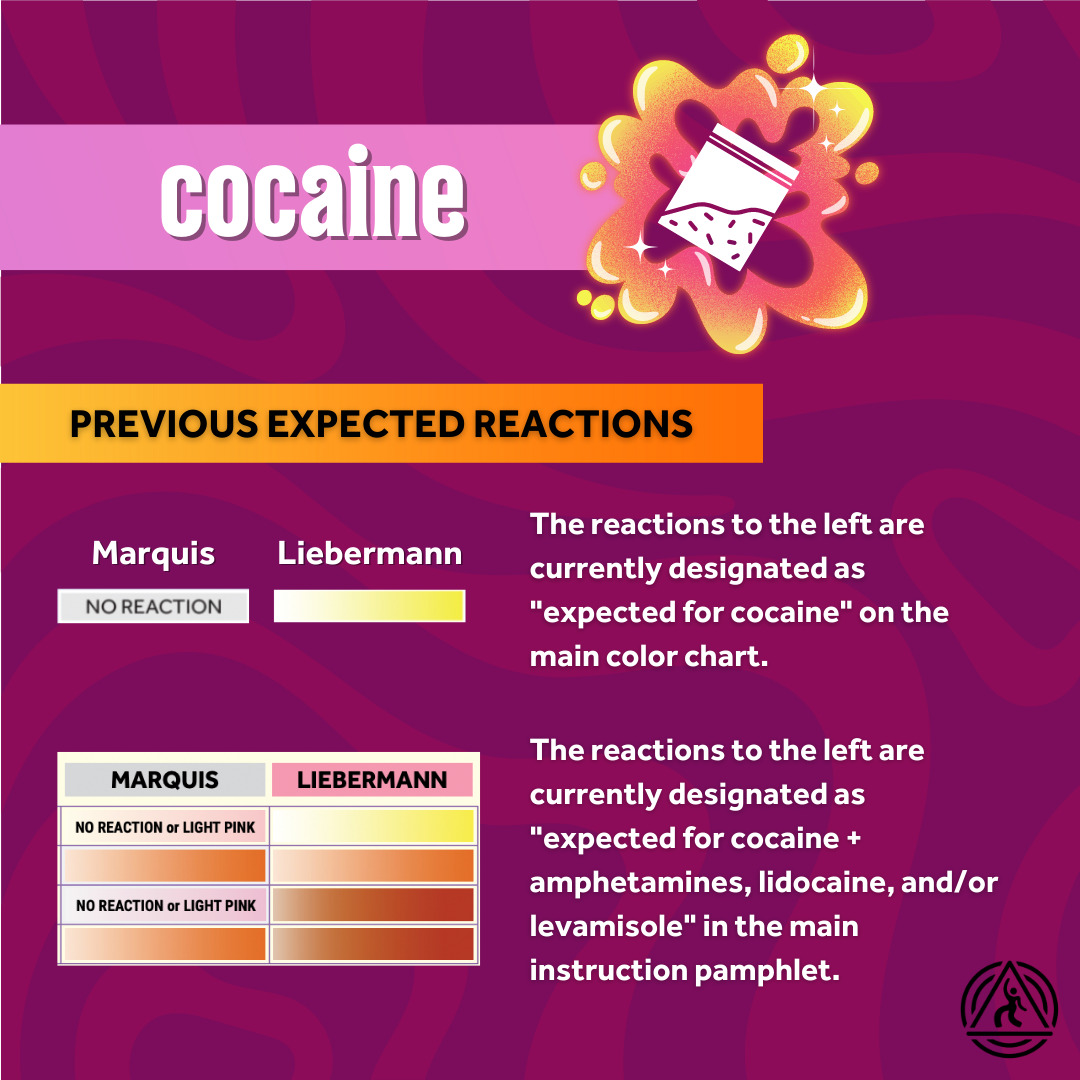

Previous expected reactions for cocaine included:

- Marquis: No reaction

- Liebermann: Light yellow

- Morris: Bright blue

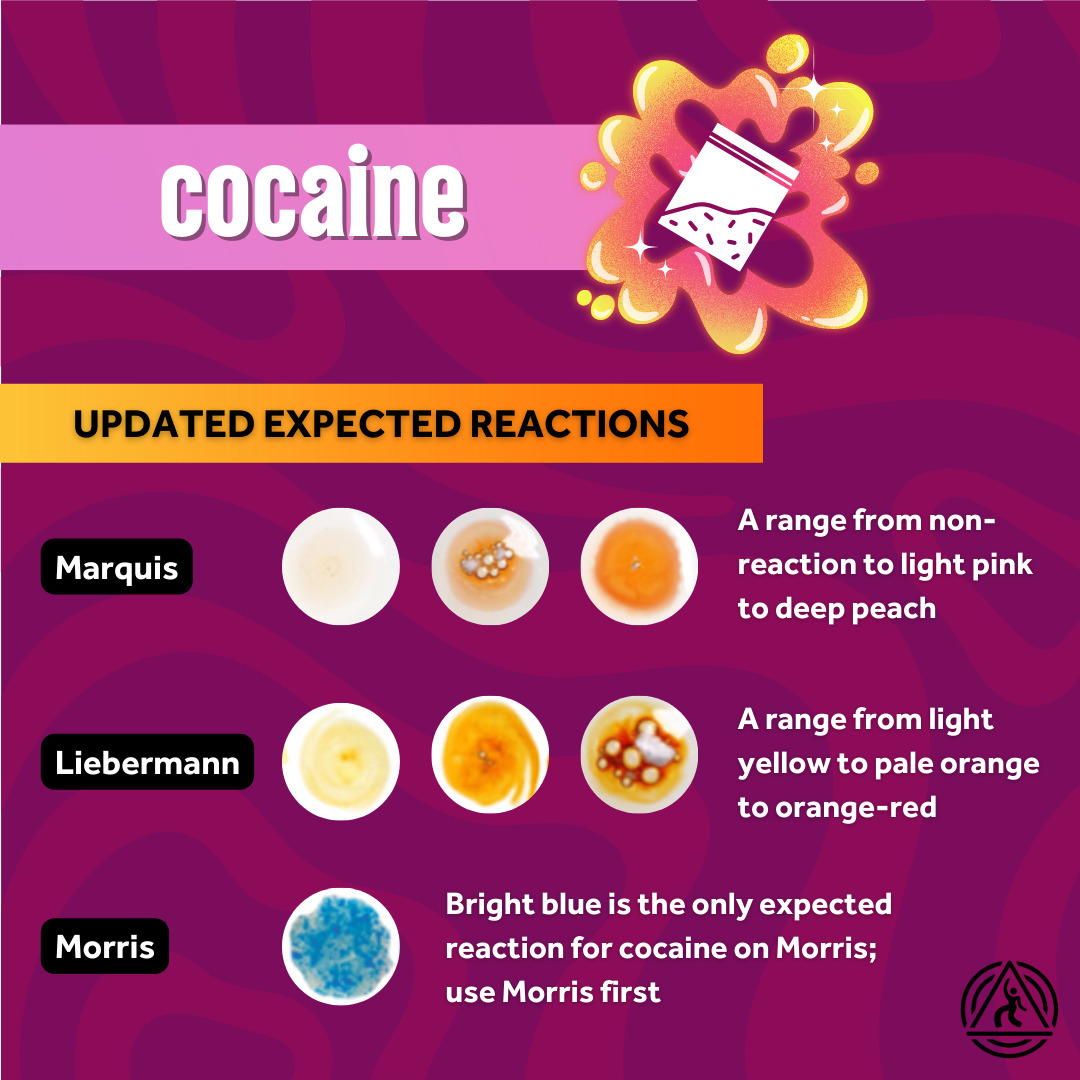

Updated reactions for cocaine are:

- Marquis: A range from no reaction -> light pink -> light to medium peach

- Note: Bright, fruity orange should be distinguished from a deep peachy color on Marquis reagent. When in doubt, use an amphetamine test strip.

- Liebermann: A range from light yellow -> orange -> brick red-orange

- Morris: Bright blue

Graphic representations of the old and new expected reactions are included in the image carousel below. Make sure to click to expand the images.

- It has historically been believed that any orange tint to Marquis reagent when testing cocaine was indicative of amphetamine(s) in the sample. In recent years, however, increased access to lab analysis by drugsdata.org has allowed us to track changes in drug markets and the resultant impacts on reagent reactions.

- We almost never see cocaine samples that present alongside amphetamine. This isn’t to say it’s impossible, or it isn’t happening, but the labs and sources we have access to have few or no entries matching exclusively cocaine & amphetamine-type substances.

- We discovered that the peachy color so commonly obtained when testing cocaine was also occurring with samples that contained no amphetamine at all.

- Initially our hypothesis was that this peachy-orange color was caused by an organic or inorganic impurity such as methylecgonidine or benzoylecgonine, but there doesn’t appear to be much consistency between samples containing one, both, or neither in terms of final color.

- At this time it is not clear what is causing this change, but we will continue to investigate it. Please reach out to rachel@dancesafe.org if you are an analytical chemist or have any information about what may be causing such a wide range of reactions.

- Several years ago, it was hypothesized that both levamisole and lidocaine would produce rusty reddish colors with Liebermann reagent. This was validated through field tests and a review of existing literature on reagent reactions for both substances.

- During our DrugsData review process we discovered multiple levamisole-containing cocaine samples that produced a bright yellow, orange-tinted color with Liebermann, not a brick-red reaction as we’d expected. This immediately discredited our working understanding that all levamisole-containing reactions would turn reddish-orange with Liebermann.

- In the meantime, DrugsData samples containing only cocaine and typical impurities and/or minor cuts such as tropacocaine did produce the brick red-orange hue we’d expected to indicate a levamisole or lidocaine cut.

- Lidocaine’s color reactions are less certain. It does appear that lidocaine consistently produces a deep reddish-orange hue with Liebermann. Further information is needed to clarify lidocaine’s role in Liebermann reactions.

- Regardless, given these uncertainties we have removed our advisory that Liebermann can be used to determine whether a cocaine sample is cut with levamisole and/or lidocaine.

- People who are immunocompromised may be at a higher risk of immune-related complications when consuming levamisole on a regular basis, and should proceed with discretion.

- People who have pre existing heart conditions are generally at higher risk when consuming cocaine. Additional (unknown) additives may have unpredictable effects on such conditions as well.

- Consumers should be aware of the high possibility of their cocaine being cut with active and/or inactive bulking agents, including lidocaine, levamisole, tropacocaine, filler, or anything else, really.

Summary: Cocaine Color Chart Changes

- All reactions listed on the “How to Test Cocaine” segment of the main 8-fold pamphlet are now considered to be “expected reactions” for cocaine. We no longer recommend trying to differentiate between reactions that may indicate the presence of possible amphetamines, levamisole, or lidocaine.

- Amphetamine test strips may be used to check for the possible presence of amphetamines in any sample sold as cocaine that turns a bright, rich orange color with Marquis reagent.

- The main color chart currently lists a non-reaction as the only expected reaction for Marquis reagent, and a light yellow to be the only expected reaction for Liebermann. These are incorrect. The cocaine reactions row on the main color chart should be disregarded entirely until further notice.

- A bright, Jolly Rancher blue Morris reaction remains the standard initial test for cocaine. Whenever testing suspected cocaine, start with Morris. Anything except a blue reaction on Morris should be considered unexpected.

- Bottom line: At this time we’re not sure what exactly causes such a broad spectrum of expected reactions with cocaine, since the samples we reviewed were, effectively, exclusively cocaine alongside some typical impurities or minor active cutting agents. Anyone with relevant qualifications or knowledge is welcome to email rachel@dancesafe.org with tips and information.

A compilation of existing expected reactions for MDA can be found here.

- MDA is rarely found alongside other drugs. We’re only really aware of it occasionally showing up alongside MDMA in the same pill or baggie.

- MDMA has reagent reactions that overshadow the reactions of MDA, so we only evaluated DrugsData submissions involving MDA on its own.

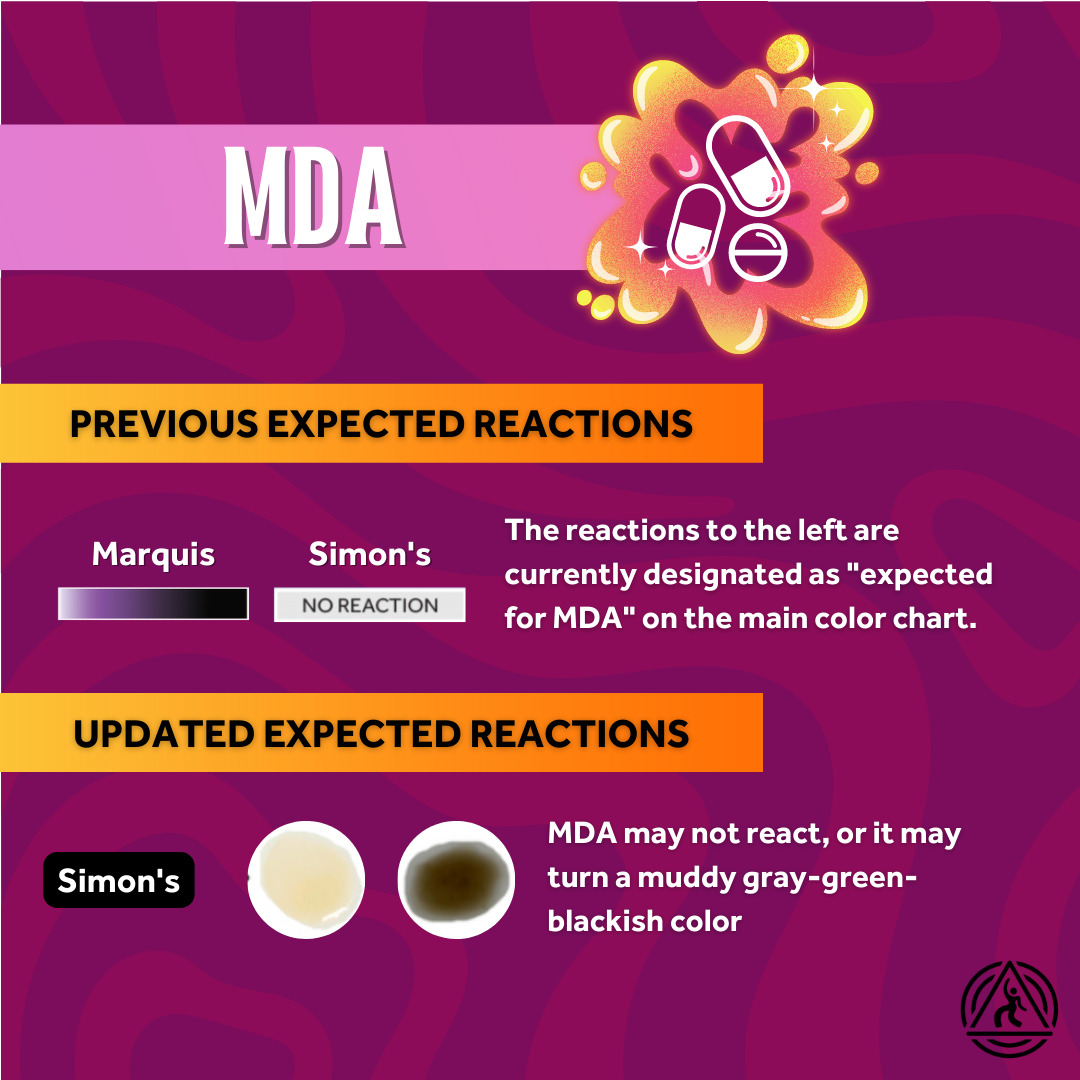

Previous expected reactions for MDA have included:

- Marquis: Purple/black

- Simon’s: No reaction

Updated reactions for MDA are:

- Marquis: Purple/black

- Simon’s: No reaction OR muddy gray/greenish/blackish

Graphic representations of the old and new expected reactions are included in the image carousel below. Make sure to click to expand the image.

- In mid-2021 we started receiving reports of an unusual Simon’s reaction we’d never encountered before: a muddy grayish, greenish, blackish color.

- We immediately launched an investigation into our existing supplies of Simon’s reagent to ensure there weren’t any issues with manufacturing. Once we’d verified there were no issues with our reagents, we started working with patrons to provide DrugsData submission codes so they could send samples to the lab for further analysis.

- All submitted samples returned as MDA. We continued tracking this supply change for several months, including testing samples on our own FTIR machines at events, and ultimately determined this new Simon’s reaction to be expected for MDA.

- We’re still not sure why this is happening, or what changed. We believe it has to do with some shift in how MDA is manufactured, washed, and/or transported.

- Remember: All two-part reagents are used by placing a drop of bottle A on top of your drug sample, followed by a drop of bottle B on top of the same drug sample.

- Do not use two-part reagents on two separate samples.

- In other words, two-part reagents should be Sample + Bottle A + Bottle B, not Sample + Bottle A in addition to Sample + Bottle B.

- Instructions are included in the 8-fold reagent pamphlet that comes with every test kit.

Summary: MDA Color Chart Changes

- All reactions remain the same except Simon’s, which may:

- Not react OR

- Turn muddy gray-green-blackish.

A compilation of existing expected reactions for 2C-B can be found here. We’re still working on validating and/or updating reactions for Folin.

- 2C-B is not commonly found alongside other drugs, so we only evaluated its reagent reactions in samples where it’s the single active ingredient.

- 2C-B has always been challenging to test with reagents, since its reactions can be very similar to those of 2C-I. Unfortunately we’ve discovered there is a much broader range of possible 2C-B reagent reactions than originally thought.

- There are a number of potential explanations for why substances that contain exclusively 2C-B as an active ingredient may have such a spectrum of color reactions with multiple reagents. We’re not in a position to solve this mystery.

- Many other substances may produce indistinguishable reactions from those of 2C-B:

- 2C-B may test as bright yellow on Marquis, muddy yellow on Liebermann, and muddy yellow on Froedhe.

- Dipentylone can also test with visually similar results that are almost impossible to differentiate.

- We’ll need to further investigate whether there are any reagent reactions that can help set 2C-B apart.

- As always, we caution consumers to test drugs sold as 2C-B (or 2C-I) as a precautionary measure only, looking for red flags that something is definitely or potentially wrong (such as Marquis turning orange) rather than seeking confirmation of having one substance or another.

- Use reagents to see if suspected 2C-B’s color reactions fall well outside the range of expected reactions listed above, seeing if something does not match.

Ideally, consumers will send 2C-B or other suspected 2Cs to DrugsData for confirmatory analysis.

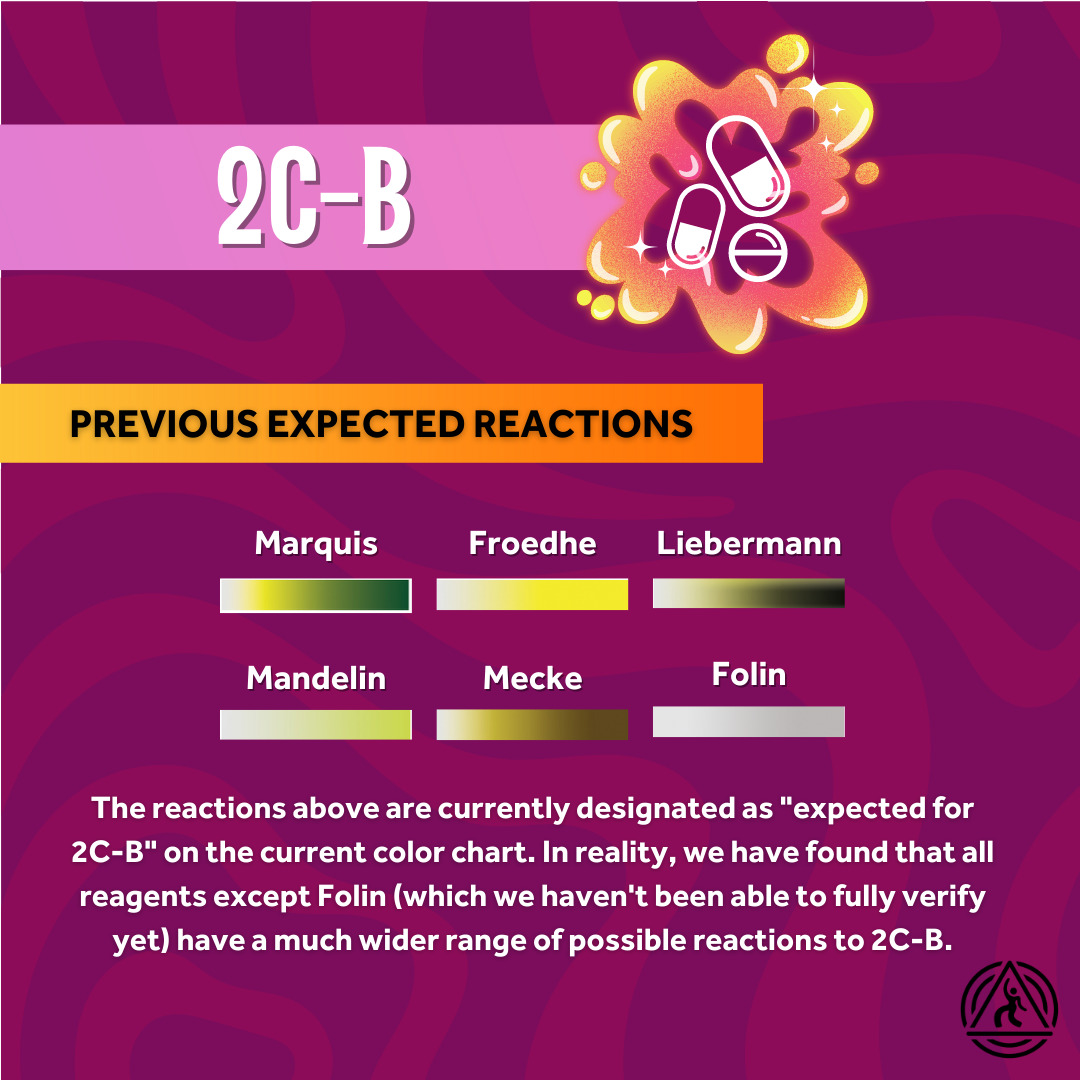

Previous expected reactions for 2C-B have included:

- Marquis: Yellow/green

- Mecke: Bright yellow to dark black/brown, and every shade in between

- Mandelin: No reaction to light yellow-mint

- Froedhe: Yellow

- Liebermann: Gradient from no reaction to yellow to black

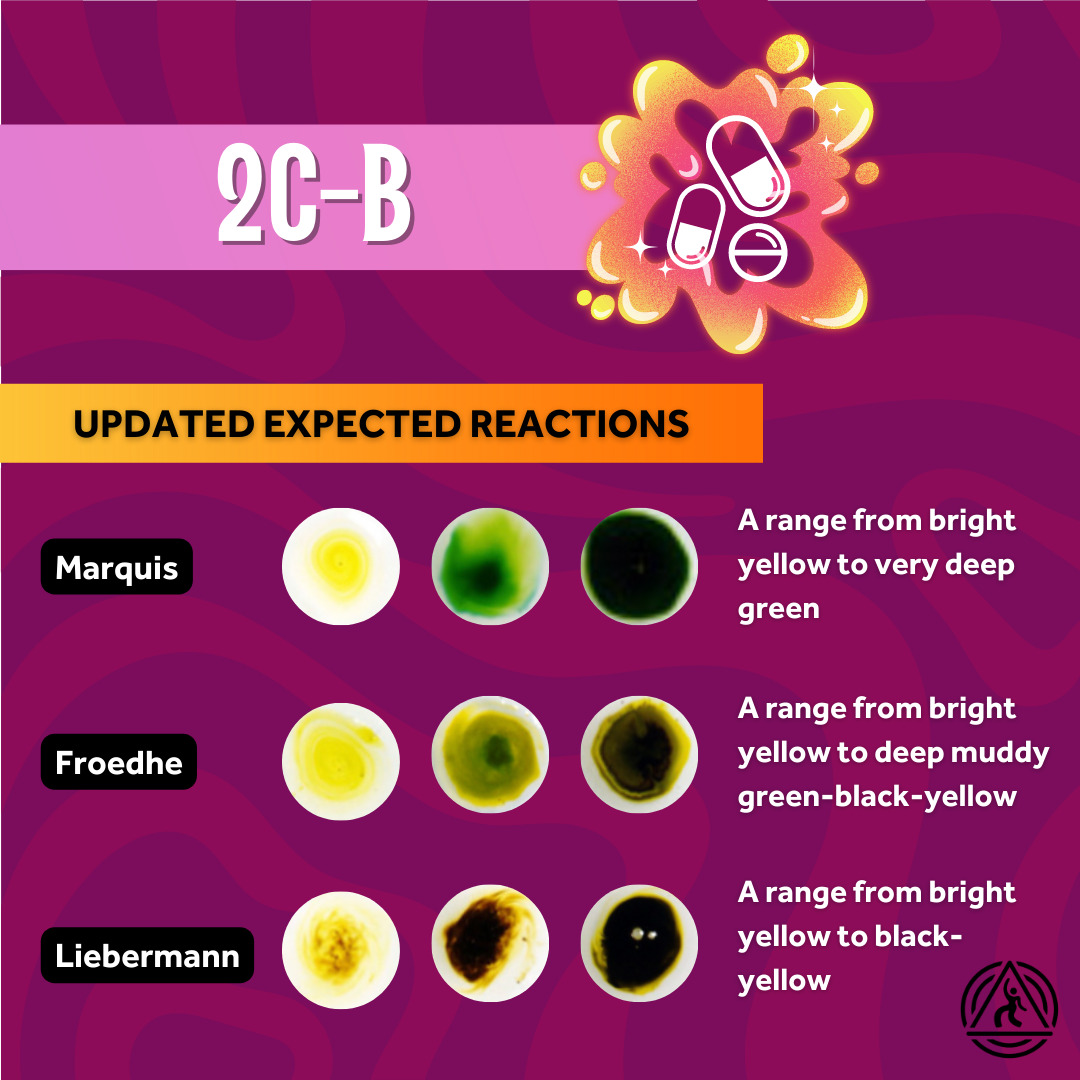

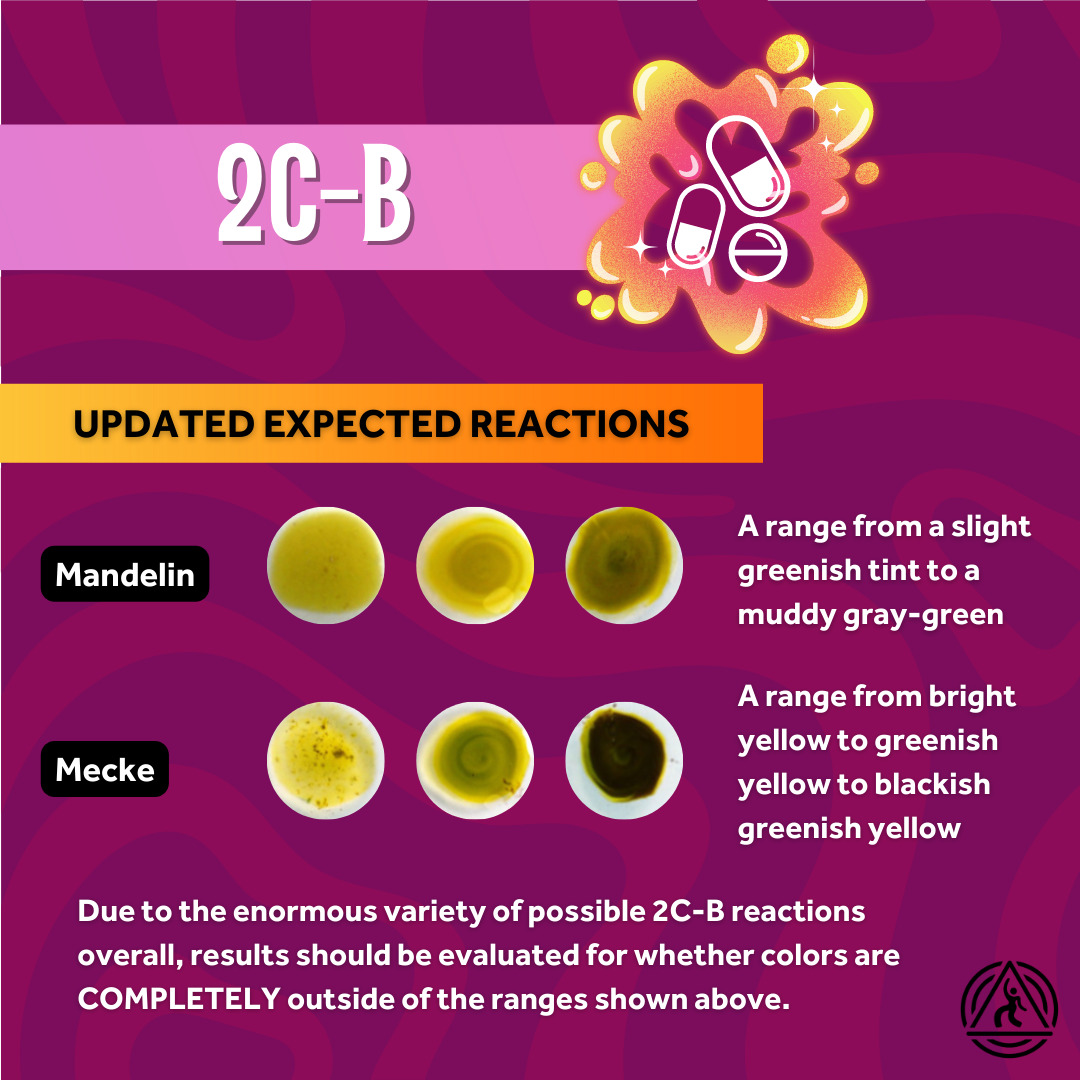

Updated reactions for 2C-B are:

- Marquis: Bright yellow to dark black/green, and every shade in between

- Mecke: Bright yellow to dark black/brown, and every shade in between

- Mandelin: Muddy light yellow to dark greenish-gray, and every shade in between

- Froedhe: Bright yellow to dark black with a yellow ring, and every shade in between

- Liebermann: Light yellow to dark black with a yellow ring, and every shade in between

Graphic representations of the old and new expected reactions are included in the image carousel below. Make sure to click to expand the images.

Summary: 2C-B Color Chart Changes

- Marquis, Froedhe, and Liebermann now have a substantial range of possible expected color reactions with 2C-B, and we’re not sure why.

- Mandelin’s reaction has been updated to include a full range from minty green to swampy yellow-green. This is tough to convey, visually, because Mandelin reagent is naturally a vibrant mustard yellow color that can make it difficult to read reactions. Always use a “blank” (drop of reagent without a sample) to compare the reaction color to the baseline reagent color.

- Mecke’s reaction has been updated to a full color range as well, from a bright lemon yellow all the way to dark black-yellow.

- Folin’s currently-listed gray reaction needs further confirmation.

- Bottom line: The current color chart is far too narrow and singular in the reactions it presents as being expected. We’ll need to figure out how to represent ranges like this in our instruction pamphlet.

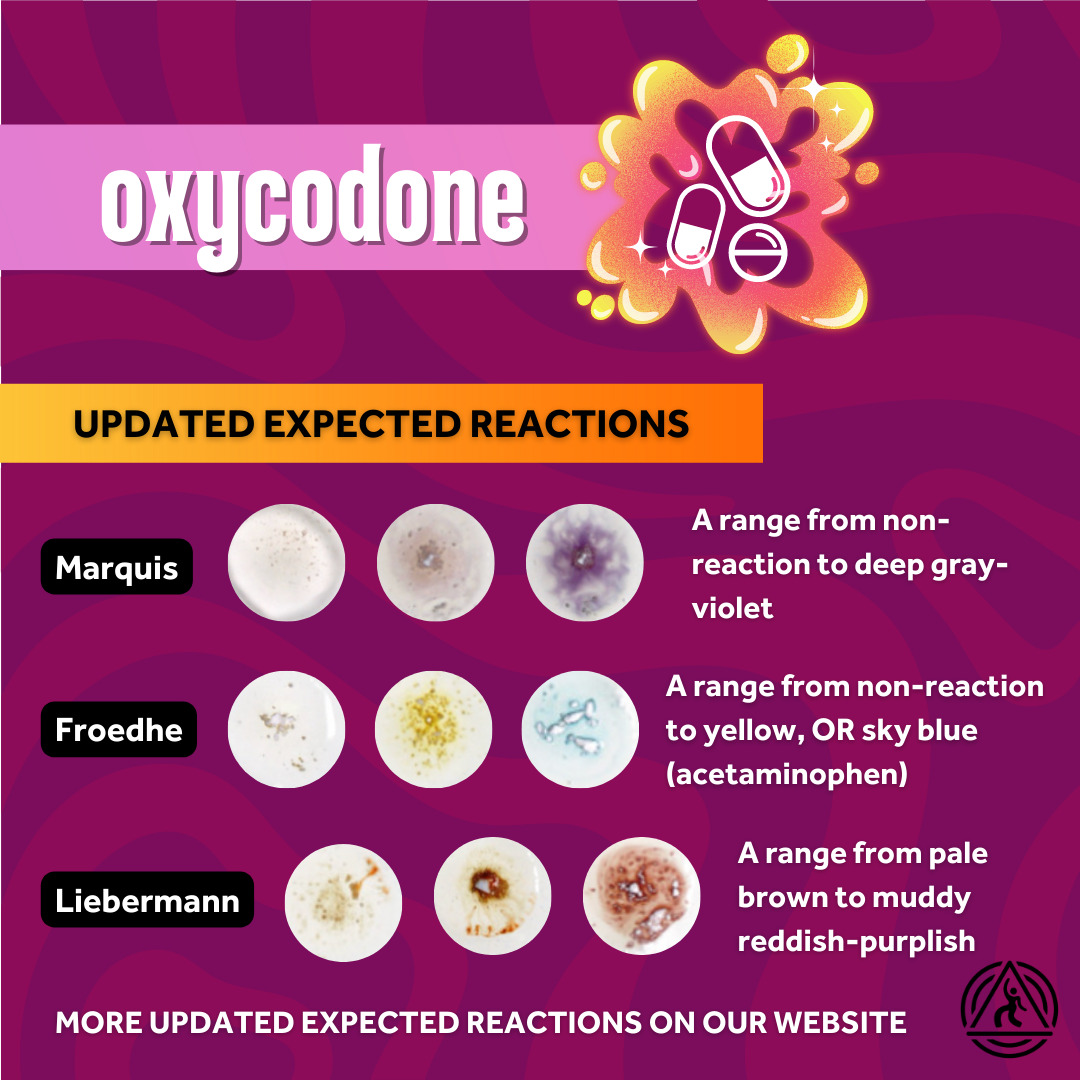

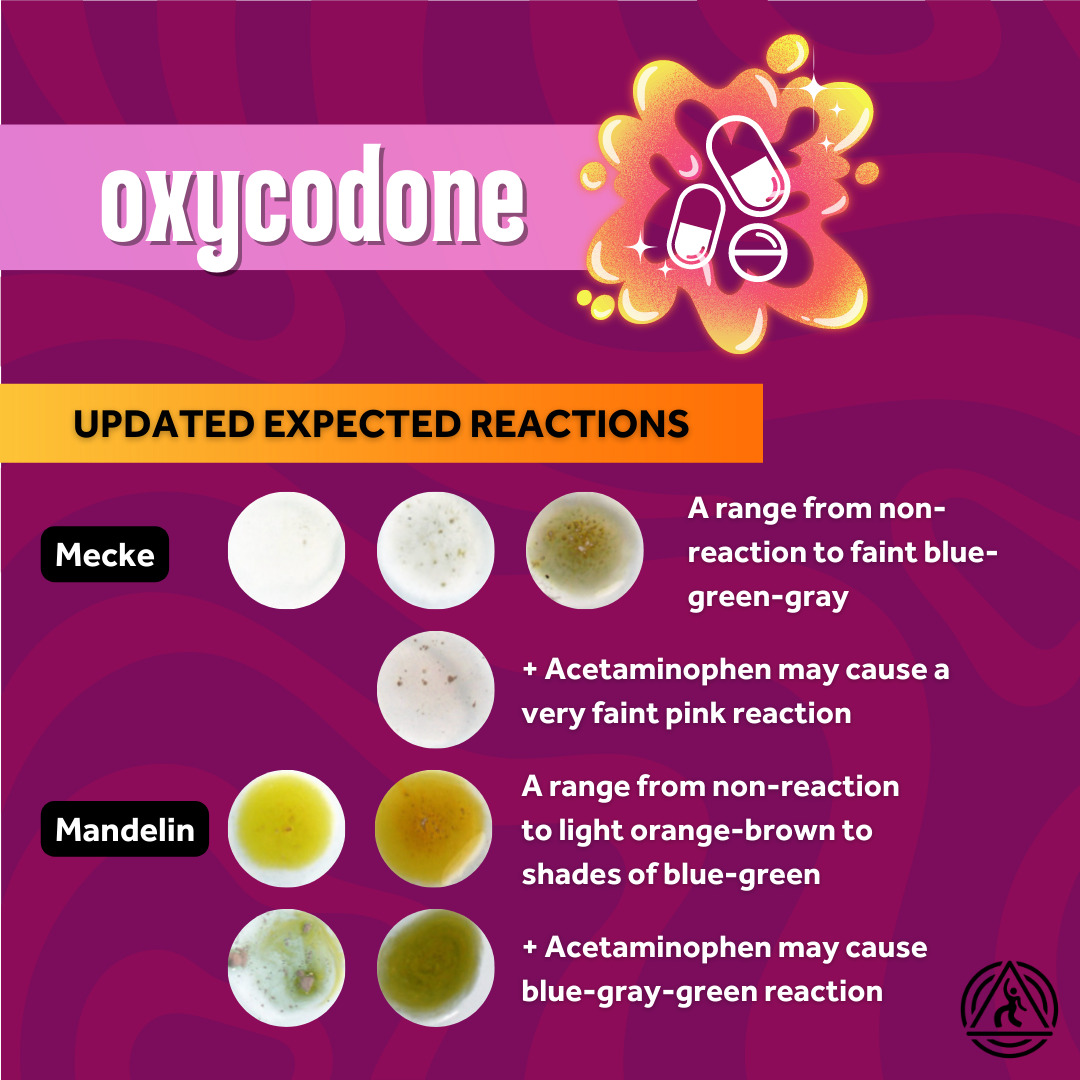

A compilation of existing expected reactions for oxycodone can be found here.

- We evaluated samples containing the following:

- Oxycodone only

- Acetaminophen & oxycodone (30:1 ratio)

- Acetaminophen & oxycodone (50:1 ratio)

- Oxycodone, palmitic acid, stearic acid

- (Note: The presence of fentanyl does not appear to impact oxycodone’s reagent reactions and is therefore not included here.)

- Oxycodone pills from non-pharmaceutical sources are notorious for being counterfeit. Illicitly-purchased oxycodone pills often contain fentanyl and/or a variety of other novel opioids, and should always be tested with a fentanyl test strip.

- Since it isn’t possible to use reagents to test for fentanyl, well-intentioned consumers may get expected results when testing their adulterated oxycodone pills but incorrectly interpret their test results to mean “good” or “pure.”

- Unfortunately there appears to be substantial variety in the possible reactions for almost every reagent. There are many novel substances and counterfeit pill presses that react indistinguishably from legitimate oxycodone.

Ideally, consumers will send oxycodone or other suspected pharmaceutical opioids or benzodiazepines to DrugsData for confirmatory analysis.

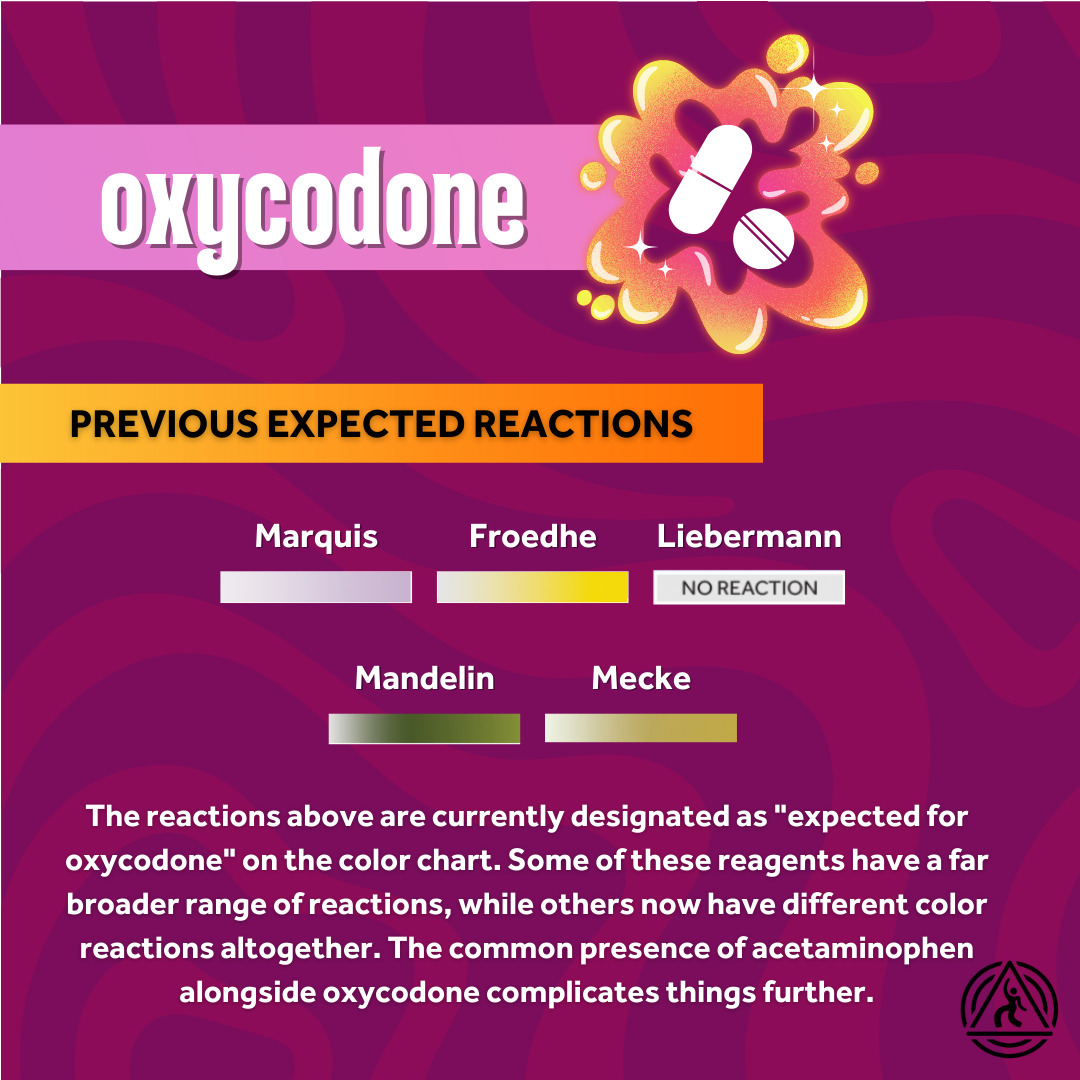

Previously expected reactions for oxycodone have included:

- Marquis: Light lavender

- Froedhe: Yellow

- Mandelin: Green-gray

- Liebermann: No reaction

Updated reactions for oxycodone are:

- Marquis: A range from no reaction -> light gray -> dusky or violet purple

- Mecke: A range from no reaction -> light blue/gray, or faint pink

- Mandelin: A range from no reaction -> very light orange -> muddy blue/green/gray

- Morris: No reaction

- Froedhe: A range from no reaction -> light yellow, or sky blue

- Liebermann: A range from no reaction -> very faint brown -> reddish-purplish-brownish

Graphic representations of the old and new expected reactions are included in the image carousel below. Make sure to click to expand the images.

- Oxycodone appears to turn different colors with Marquis depending on whether it appears alongside acetaminophen, which is very commonly pressed into both legitimate and counterfeit pills.

- Pills containing exclusively oxycodone sometimes do not react with Marquis, sometimes turn a light gray-purple, and sometimes turn a brilliant violet color. We don’t know why this happens. It may be due to end-products remaining from the manufacturing process.

- In the majority of the acetaminophen-containing pills we looked at, oxycodone appeared less likely to react with Marquis reagent.

- Many substances do not react with the Marquis reagent. A Marquis non-reaction (or light purple reaction) can have many meanings. This being said, a reaction that is distinctly not anywhere along the spectrum from non-reaction to dusky purple (such as a yellow reaction or anything that’s brightly, differently colored) is a useful immediate red flag.

- Pills and bags containing exclusively oxycodone reacted in a range from non-reaction all the way to a muddy gray/blue/green color.

- Mixtures of acetaminophen and oxycodone appeared to be more likely to react with a very faint pinkish color. It’s unclear why this happens.

- Oxycodone-only samples typically did not react or turned a very light orange-brown color, which may be hard to distinguish from the naturally yellow hue of Mandelin reagent. Always use a “blank” (drop of reagent on the plate without a sample, to compare the natural reagent color to the reaction color) when testing to help avoid misinterpreting a non-reaction.

- Older samples of oxycodone appeared to turn a more lime green hue with Mandelin reagent, but we suspect this might be because of the lighting used to capture DrugsData photos before 2019.

- Samples containing both acetaminophen and oxycodone very consistently produced a muddy gray/green/brown color on Mandelin. This color seems to darken with higher concentrations of acetaminophen.

- Froedhe’s reaction to oxycodone-containing samples appears to be very dependent on whether acetaminophen is also present.

- Acetaminophen consistently produces a sky blue color with Froedhe. Counterfeit pill presses containing acetaminophen, however, may still react with a sky blue color on Froedhe even if there are multiple other things present.

- Samples without acetaminophen more consistently produced colors ranging from non-reactions to yellows.

- Similarly to Froehde, Liebermann is less useful when testing oxycodone because acetaminophen seems to strongly influence the reaction.

- Acetaminophen typically produces a reddish-purple color with Liebermann, which significantly darkens the end reaction.

- Oxycodone-only formulations seem to have a range of expected colors with Liebermann, from non-reactions to a reddish-brownish hue.

Summary: Oxycodone Color Chart Changes

- The range for Marquis needs to be expanded as a gradient of possible reactions, from non-reaction all the way to a brighter purple.

- Mecke is currently listed as having an expected desert brown-green color on the chart, which needs to be updated to include a spectrum from non-reaction to brown-green. We will also need to figure out how to incorporate the possibility of an outlier “faint pink” reaction with certain acetaminophen-containing samples.

- Mandelin’s current color on the chart does match one possible deeper forest blue-gray-green that may be produced by certain acetaminophen-containing samples, but it needs to be updated to include the range from non-reaction to light brown to blue-gray-green.

- The currently listed yellow-only reaction for Froedhe needs to be updated to include a range from non-reaction to yellow, and account for the sky blue color caused by some acetaminophen-containing samples.

- Liebermann is incorrectly listed as having non-reactions with oxycodone. Liebermann typically turns some very light/subtle shade of light brown (probably due to the very small amount of actual active oxycodone in these pills compared to binder/filler ingredients) but may also turn a deep purple-red-brown with acetaminophen-containing samples.

- Acetaminophen deeply complicates the oxycodone testing process because it may or may not be present in illicit bags/pills. Since it has its own distinct set of reactions with these reagents, end-results may contain confusing color blends that aren’t possible to read effectively.

- For the time being, we’ll be releasing alerts on our socials as well as notices on our shop pages that link to this blog post.

- We’re working out some logistical kinks around designing and including printed inserts that will come with all reagent purchases until we can update the entire instruction pamphlet, which is a major project in the works for this year.

- The next round of instruction prints will include quick-fix, essential changes based on the information in this article.

Tracking reagent reactions has always been a matter of following drug markets closely and being as responsive as possible when things change. We update our materials and recommendations as soon as new information comes to light. Our previous set of expected reactions was the product of quite a lot of investigation, research, and observation over a very long period of time; all of our drug checking materials always reflect our best knowledge at the given moment.

Mixtures, precursors, adulterants, novel substances, impurities, diluents, and all sorts of other curveballs can make it extremely difficult to identify a standard set of expected reactions for a given drug, and accurate reactions may become inaccurate (or be discovered to be inaccurate) down the line as things change. We make it as simple as we possibly can, but the reality is that drugs aren’t simple. We’re responding to a market that can shift in a matter of hours while doing highly stigmatized work with limited resources.

Drug checking is complicated, and the information provided by at-home drug checking tools like reagents and test strips can be frustratingly limited. It’s much more satisfying to test a substance and say “it’s this drug, specifically!” than it is to say “it’s reacting as expected, but that’s all we know.” It’s also much more satisfying to purchase a drug checking product that promises certainty, with strong language like “x is y if your color is this” or “identify the exact percentage of x drug in your sample in just five minutes!”.

We all want to approach a drug experience with the confidence that we did our due diligence, we tested our substances, and now we know what we’re dealing with. No one’s at fault for wanting to have a little bit of certainty about what we’re putting in our own bodies. The tricky part is recognizing that certainty is almost impossible when we’re purchasing drugs on the illicit market.

Drug checking can (and does!) tell us valuable information, but it’s typically information about unknowns rather than knowns. Using these tools correctly therefore requires an understanding of the importance of being aware of the unknowns.

The goal of at-home drug checking is to come away with information that is trustworthy in its contents and honest in its limitations – it’s not about feeling good or satisfied. In fact, properly conducted at-home drug checking often isn’t very satisfying because it’s not a tool for certainty (which our brains love). Instead, it serves as a reminder that prohibition puts us all in a position of being unable to consent to the contents of the drugs we’re taking, despite our best efforts. Drug checking is a tool for improving our informed consent.

Behind the scenes at DanceSafe we learn something new about drug checking every single week, even those of us who have been testing drugs for a decade or longer. Using reagents and test strips is, and always has been, a band-aid solution to a real systemic problem: your drugs could be – literally – anything, and it’s because drug production has been forced underground into an illicit market. Prohibition puts people in a position of using complex forensic tools, at home, without explicit training, in an effort to protect themselves and their loved ones. It also forces drug checking professionals to be on a constant quest for the newest information while reagent reactions and drug mixtures change on a daily basis. To add insult to injury, drug checking tools are criminalized in many states. It’s pretty much a mess.

In this discussion we’ll outline some of the main complexities of drug checking. We’ll then advise on a few key points of mental reframing that, with any luck, will help you better understand the tools you’re using.

(We strongly recommend reviewing our newly-released drug checking FAQ sheets, which will soon be rolled out in binders for DanceSafe drug checking patrons to read as they get their drugs tested. These sheets may answer some or all of your questions. The Google Drive link above will always contain the most updated versions of the FAQ sheets.)

Complexities of Drug Checking

- There are tens of thousands of drugs, and any given reagent may react with multiple substances in the same way.

-

-

- As you saw in the 2C-B and oxycodone reaction updates provided above, several reagents may have the exact same set of reactions with multiple drugs, making it impossible to distinguish between them.

- Darker reagent reactions may overshadow lighter reactions, masking the presence of two or more things in a sample.

- Novel substances may have reagent reactions that are indistinguishable from those of popular drugs, despite having different effects, dosages, and safety profiles. Novel substances enter the market on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis.

-

- “Expected reactions” are a set of reactions we typically expect to see with a particular substance, but they’re not foolproof.

-

-

- Little things, however, may occasionally make a reaction appear “unexpected” despite the actual substance not being contaminated or adulterated.

- For example, a drug might be made poorly and contain non-psychoactive impurities (which don’t get you high at all) that react with reagents in their own unique ways. This might make a reaction look unexpected even though your drugs are not actually adulterated.

- Example: The updates we’ve just made to our MDA and cocaine reactions were based upon shifts in the market that made unadulterated samples appear “unexpected.”

- We’re always on the lookout for changes like this. We keep a close eye on drug trends and try to update our expected reactions as often as possible (like right now).

-

- The drug market matters – a lot.

-

-

- Some substances, like MDMA, have very consistent reagent reactions that haven’t changed over time. By keeping an eye on MDMA market trends we’re able to loosely evaluate the likelihood that MDMA would be found in addition to other drugs under a certain set of circumstances, or whether there are other substances cropping up that may have indistinguishable reactions from those of MDMA (and therefore warrant concern).

- Being able to evaluate the contextual likelihood of a reagent result meaning one thing or another is a skill that requires having access to lots and lots of specific resources and time.

- Drug markets are global, national, and regional, but they’re also very dependent on the specific place someone is located in, even down to the neighborhood.

- The Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, for instance, has a drug supply that’s unique to the entire world right now. Its drug supply would be totally different than that of Skid Row in Los Angeles, or Coachella on Friday night in 2022 versus Saturday night in 2023.

- Knowing about the MDMA supply in the EDM community of southern California is not the same as knowing about the MDMA supply in the EDM community of Ohio, or the underground rave scene of Ohio, or among people in Ohio who don’t go to raves but know people who do, or among people in Ohio who have never tried molly before and are buying it from someone they met in a bar, versus a club, versus a bus stop, versus Instagram, and so on, and so forth. Every 10-minute walking distance from neighborhood to neighborhood can dramatically change the drug landscape.

- Drug markets are extremely granular – and being aware of certain major global events can help paint a picture of what substances are being produced, where, why, and how. A famous example of this is the great MDMA shortage of the early 2010s, which happened because of mass destruction of sassafras oil and MDMA in Cambodia. Many novel cathinones entered the market temporarily, until the rise of new precursors allowed MDMA to be made more freely without relying on safrole oil and the global supply ballooned once more.

- Drug markets are global, national, and regional, but they’re also very dependent on the specific place someone is located in, even down to the neighborhood.

- Tracking these trends on a global level takes an exceptional amount of reading and energy. Even trying to keep a finger on the pulse of something as specific as, for instance, the production of dextroamphetamine in the United States devolves into an impossibly complex web of intersectional topics, ideas, and necessary background knowledge.

- Many, many people working full-time jobs could put their heads together just on the isolated issue of dextroamphetamine production in the United States and still be missing almost the entire picture.

- All we can really do is make elevator pitches and give summary explanations of what we think is generally happening. And we are always missing so much information, no matter how much effort is involved.

- Our current understanding of things changes on a daily basis. It’s a lifelong game of running, catching up, releasing statements, and hitting the road once more.

- All this to say: Any one person using drug checking materials at home cannot possibly be expected to have enough contextual knowledge about drug markets to be able to determine whether the light yellow ring around their black Marquis reaction is likely due to a new precursor, a wash, an adulterant, an organic impurity, an inorganic impurity, a mixture, a dye, some crumbs on the testing plate, or a novel substance. And we don’t expect you to. But it’s important to understand just how much background information goes into a statement as simple as “Based on the current drug market and these reagent reactions, I think it’s contextually likely that this MDMA sample contains exclusively MDMA.” That is, truly, about as much certainty as you could possibly ask for about a reagent reaction, and for it to hold weight it would need to be informed by thousands of hours of investment in this specific topic.

-

- Picking apart the various pieces involved in reagent reactions requires a very wide and intersectional spread of knowledge. In other words, drug checking must be a collaborative effort between people who have different specializations.

-

-

- For instance: “rocks” of crystal can be the product of “re-rocking,” where a chemist re-forms a crystal that may contain multiple substances. Having a background in chemistry is essential for understanding this possibility, but having a background in drug markets is essential for understanding the likelihood of a chemist engaging in such a practice for a particular drug, and the likelihood of various substances ending up in the final rock, and the likelihood of that final rock testing in an unexpected or expected way as a result.

- Contextual knowledge: MDMA is contextually unlikely to be “re-rocked” based on the current market and the availability of MDMA in general, so a nickel-sized crystal that tests as expected with reagents is contextually likely to contain exclusively MDMA, though not guaranteed.

- Contextual conclusion: For this reason, chunky crystals of MDMA are likely to be a more reliable purchase choice for people who are looking to buy something that contains exclusively MDMA.

- Contextual knowledge: Ketamine precursor A is a non-psychoactive manufacturing intermediate that frequently appears alongside ketamine in DrugsData submissions.

- Contextual conclusion: Despite initial concerns that ketamine precursor A might be making Morris reactions appear more “blurple,” conversations with chemists have deemed this to be a contextually unlikely explanation for the range in Morris color reactions.

- Contextual knowledge: Evaluating the prevalence of fentanyl in non-opioid drugs is a collaborative effort between thousands of people across the US, including on-the-ground social service programs, individuals, researchers, public health departments, lab techs, and EMS. Each audience has a very specific flavor of exposures, experiences, biases, information, and missing links.

- Contextual conclusion: The only way we’re able to collect even a remotely accurate picture of where fentanyl is in the drug supply is remaining in constant communication with all those audiences.

- Contextual knowledge: People who use drugs of all kinds have unique insights into the ways they wash, prep, ingest, and otherwise test their own substances, sometimes illuminating current manufacturing trends or solving mysteries around changes in the market.

- Contextual conclusion: The lived experience and subjective information shared by people who use drugs is just as important in the grand scheme of things as the sanitized lab work conducted by researchers and folks “off the ground.”

- Contextual knowledge: MDMA is contextually unlikely to be “re-rocked” based on the current market and the availability of MDMA in general, so a nickel-sized crystal that tests as expected with reagents is contextually likely to contain exclusively MDMA, though not guaranteed.

- For instance: “rocks” of crystal can be the product of “re-rocking,” where a chemist re-forms a crystal that may contain multiple substances. Having a background in chemistry is essential for understanding this possibility, but having a background in drug markets is essential for understanding the likelihood of a chemist engaging in such a practice for a particular drug, and the likelihood of various substances ending up in the final rock, and the likelihood of that final rock testing in an unexpected or expected way as a result.

-

- When it comes to drugs and drug checking, there is almost never one singular, simple answer that works across the board for any given question.

-

- Will fentanyl test strips work when testing black tar heroin, which has a different consistency and might prevent the liquid from traveling up the testing pad?

- Do lab-grade analytical samples of drugs react the same way on reagents that illicitly-manufactured drugs do? So, can we establish accepted reagent reactions based exclusively on lab-grade analytical samples? (Short answer: Definitely not.)

- Is NIR more effective than FTIR when testing pharmaceutical samples, but less effective when testing street samples?

- Could GC/MS still miss fentanyl in the baggie unless someone crushes and shakes the submission before sending it in? (Are some test strips even more effective than GC/MS for that reason?)

- Could a particular drug be transdermally absorbed through this one very specific and unlikely edge case? Did that actually happen in a given situation?

- Did this autopsy report misrepresent the drugs involved because there’s no distinction between cross-contamination or someone who simply took multiple different drugs?

- Is that immunoassay strip result based on a GC/MS library, or using a urine test?

- How many drugs did the coroner look for while running a toxicology screen? What library was available? Did public health funding impact the reference samples used due to the expense involved, and therefore miss something like xylazine because it’s less regionally important?

- Did that person have a pre existing health condition that raised or lowered their resting heart rate or respiratory rate?

- When that person’s pupils were checked, was it by someone who knew how to properly check for reactivity instead of just holding a light over their eyes?

- Does humidity impact the amount of time Ehrlich’s takes to react?

- Do immunoassay test strips work the same way when testing urine as they do testing drugs?

- Is purple MDMA the result of getting transported in wine, being intentionally dyed, or a poor manufacturing process?

- Are DrugsData reagent results an accurate portrayal of the drug market, given that people have to 1) know DrugsData exists in the first place and 2) have the money to send in a sample?

- What communities have submitted their drugs for checking?

- Who might be afraid to submit samples because of systemic violence, and therefore be underrepresented?

- Could DrugsData have misidentified a novel cathinone because another similar, more popular cathinone has an indistinguishable result?

- Was that medical emergency the result of someone having a panic attack after smoking weed, smoking a PCP-dipped cigarette (regionally relevant), or smoking a novel cannabinoid sprayed onto CBD-only weed (also regionally relevant)?

- Did someone hide their opioid use and claim they’d only smoked weed, despite having taken a counterfeit oxy pill that led to overdose, due to fear of punishment?

- Was more naloxone needed because a more potent opioid was used, or because someone didn’t wait long enough to administer more doses, or because the person had also consumed another sedative like xylazine or diphenhydramine, or because someone had a preexisting respiratory condition?

- Is the pill crumbly because it’s been stored in a bag in someone’s glove box, or because it’s counterfeit?

- Do LSD adulterants and blotter dyes also glow under blacklight, making this DIY testing method unreliable? (Answer: yes!)

- Did the reagent smoke and bubble because a substance is very concentrated, or because the powder was crushed extra finely?

- Could this ketamine have been re-rocked with 2-FDCK? Is 2-FDCK off the market entirely because a major distributor shut down, or did someone start producing it again in the last week and a half?

- Is the reagent a little bit old, making a non-reaction look like a reaction?

- This list could go on forever. We tend to view our knowledge about drugs as though we have a few dark splotches in a sea of light, but we are truly in a sea of darkness attempting to navigate based on a few patches of stars. (And the stars move, and get covered by clouds, etc.)

There’s much more we could say about the complexities of drug checking, but it would take many, many hours of content. It’s impossible for everyone to know everything. Really, it’s impossible for anyone to know everything about anything, let alone everything about multiple intersecting topics. No one on the DanceSafe team does, that’s for sure.

And that’s really the point of this article. Within our team we have many highly specialized individuals, and some of those individuals are specialized in collecting and disseminating information from other specialists. We rely on each other, deeply and completely, to make drug checking work at all. No one has all the answers. Hopefully DanceSafe can, at the very least, serve as a trustworthy resource of summarized information that’s collected from specialists in an effort to Frankenstein together something that makes sense.

Now: a summary of some mental reframing we suggest to help make drug checking make more sense in this larger context.

Mental Reframing

- Misrepresentation and adulteration are not intrinsic to drug markets (the pharmaceutical industry is an easy example of this). They’re the inevitable outcomes of prohibition. This process of iterative updates will continue literally forever, as long as prohibition continues.

- As we’ve said, it’s important to look at reagent and test strip drug checking in terms of red flags, not green lights. There are an infinite number of unknowns in the drug market; despite this, we can use these tools as watchdogs for obvious or potential unexpected issues with our drugs.

- There’s more about this in the Drug Checking FAQ section of our website (and the FAQ sheets linked at the top of this article), but we can generally categorize reagent results into being “expected” or “unexpected” given our current understanding of expected reactions. Within this, we can categorize unexpected reactions as being “clear” (something is absolutely, definitely not right) or “unclear” (something might be off, but we’re not sure).

- Example: MDMA turns yellow on Marquis reagent instead of black. There’s no way a black reaction is hiding underneath that yellow reaction, so this is a clear red flag. Something’s up.

- Example: MDMA turns black with a yellow ring on Marquis reagent. You clean your testing plate off (just in case) and try again, but get the same result. This is an unclear red flag; you’re not really sure what it means, and you understand that without the help of a lab you’re dealing with an unknown situation.

- In both of these cases, you can decide if you consent to these unknowns and still want to proceed.

- You might decide to send a sample to a lab.

- You might take a lower dose than usual.

- You could spend some time reading about how to identify signs of stimulant, depressant, and opioid overdose, and share that information with your loved ones.

- You may choose to call a friend and ask them to stick around with you until you’ve fully come up on your dose.

- You could call the Never Use Alone phone line.

- Understanding unknowns gives you the ability to put additional protections in place. These measures can and should be taken even when you get expected results.

- In both of these cases, you can decide if you consent to these unknowns and still want to proceed.

- There’s more about this in the Drug Checking FAQ section of our website (and the FAQ sheets linked at the top of this article), but we can generally categorize reagent results into being “expected” or “unexpected” given our current understanding of expected reactions. Within this, we can categorize unexpected reactions as being “clear” (something is absolutely, definitely not right) or “unclear” (something might be off, but we’re not sure).

- Try to come away from a test with the mentality of feeling empowered in these unknowns.

- It’s one thing to take a drug with absolutely no idea that you’re in the dark about a lot of things, no matter how confident your plug is. It’s another to take a drug while consenting to the sheer volume of information you’re missing. This allows you to set up your environment, prepare for uncertain outcomes, and think critically about how you can mitigate the inherent risks of the illicit drug market.

- Your decision to test your drugs is an act of love, for yourself and others. You won’t have all the answers when you’re done, and you won’t come away with certainty, but that’s not the point. The idea is to do what you can with what’s available and respond mindfully, intentionally, and consensually based on the information you can get from drug checking.

- Don’t underestimate the power of red flags.

- We see it time and time again: someone comes into the booth and says “I know it’s good, but [my friend] insisted we come to test it, so here I am,” then gets an unexpected test result. This moment can change everything.

- As we’ve said, drug checking and the inherent uncertainties it holds expose us to an extremely uncomfortable truth: things might not be what they seem, and despite our best efforts, we may be powerless to know it.

We can’t understand drugs – at all – without accepting how little certainty we have and adjusting our behaviors, messaging, and communication in response. There is so much more power in saying “I don’t know” than feeling destabilized when deeply-held certainties are challenged. After all, we’re all just trying to figure it out.

With love,

DanceSafe